Why Understanding Decompression Sickness Could Save Your Diving Career

Avoiding decompression sickness is essential for every diver. This serious condition affects an estimated 3 out of every 10,000 sport dives, with commercial divers facing even higher risks.

Quick Prevention Checklist:

- Ascend slowly - no faster than 30 feet per minute

- Always do safety stops - 3-5 minutes at 15 feet

- Stay hydrated before and after diving

- Use conservative dive profiles within computer/table limits

- Wait 12-24 hours before flying after diving

- Avoid alcohol and strenuous exercise post-dive

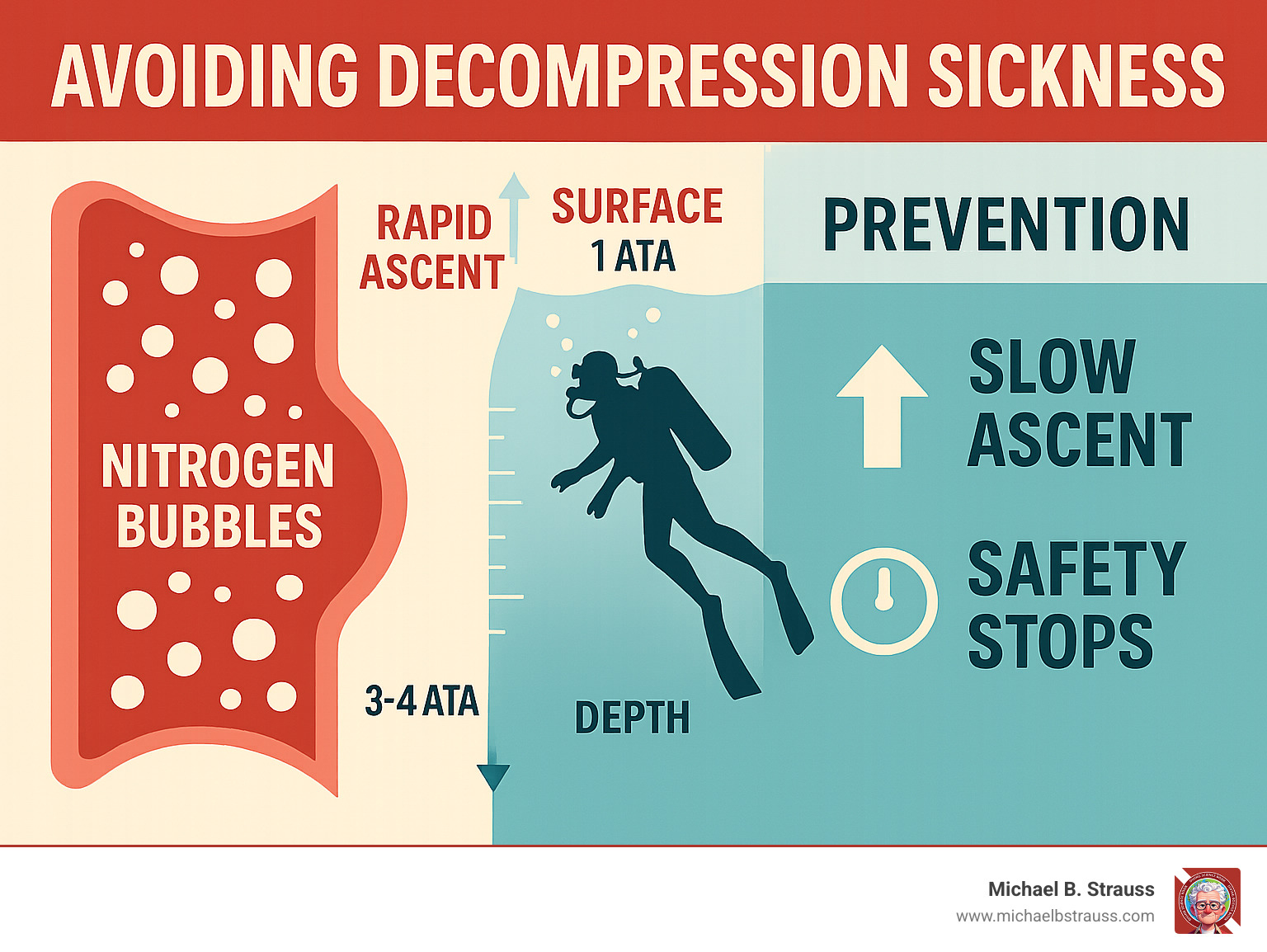

Decompression sickness (DCS), or "the bends," occurs when nitrogen bubbles form in blood and tissues during a rapid ascent. The condition gets its nickname from the hunched-over posture divers assume to relieve severe joint pain. Type I DCS causes joint pain and skin issues, while the more dangerous Type II DCS can affect the nervous system, lungs, and heart, becoming life-threatening.

Research shows about 75% of cases develop symptoms within the first hour after surfacing. The good news is that proper decompression techniques can prevent DCS entirely.

Symptoms, Types, and Key Risk Factors

Understanding DCS symptoms and risk factors is the first step in prevention. Symptoms usually appear within 15 minutes to 12 hours after surfacing.

Common Symptoms of Decompression Sickness:

- Joint pain: The classic "bends," often in knees and elbows.

- Skin rash: A mottled, itchy rash (cutis marmorata).

- Dizziness, headache, or extreme fatigue.

- Tingling, numbness, or weakness in extremities.

- Cognitive issues: Confusion or difficulty concentrating.

- Nausea or shortness of breath.

- Severe symptoms: Paralysis, difficulty urinating, or ringing in the ears.

Types of Decompression Sickness:DCS is classified by severity:

| Feature | Type I DCS (Mild) | Type II DCS (Severe) |

|---|---|---|

| Affected Systems | Skin, musculoskeletal system (joints, muscles), lymphatic system | Nervous system (brain, spinal cord), inner ear, pulmonary, cardiovascular system |

| Common Symptoms | Joint pain ("the bends"), skin rash (mottling, itching), mild swelling | Paralysis, numbness, tingling, vision disturbances, dizziness, confusion, severe headache, unconsciousness, difficulty breathing ("the chokes"), inner ear problems (vertigo, hearing loss) |

| Severity | Less severe, rarely life-threatening | Potentially life-threatening, can lead to permanent damage or death |

| Urgency of Treatment | Urgent | Emergency (requires immediate treatment) |

A third form, Pulmonary DCS ("the chokes"), affects the lungs and is a life-threatening emergency requiring immediate medical intervention.

Key Risk Factors for DCS:Several factors can increase a diver's susceptibility to DCS:

Dive Profile:

- Deep or long dives: Increases nitrogen absorption.

- Rapid ascents: The primary cause of DCS, preventing safe off-gassing.

- Repetitive or saw-tooth dives: Increases the body's overall nitrogen load.

Physiological and Behavioral Factors:

- Dehydration: Impairs circulation and nitrogen elimination. Alcohol consumption worsens it.

- High Body Fat / Poor Fitness: Fat tissue retains more nitrogen, and poor circulation is less efficient at off-gassing.

- Cold Water: Constricts blood vessels, slowing nitrogen release.

- Strenuous Exercise: Vigorous activity before, during, or after a dive can increase bubble formation.

- Fatigue: Impairs the body's ability to manage nitrogen effectively.

- Patent Foramen Ovale (PFO): A heart condition that can allow bubbles to bypass the lungs' filtering ability, significantly increasing risk. Consult a diving medicine specialist if you have a PFO. Scientific research on PFO and DCS risk shows a clear link.

- Flying After Diving: Ascending to altitude too soon can cause residual nitrogen to form bubbles.

A Diver's Guide to Avoiding Decompression Sickness

Avoiding decompression sickness is about smart planning, following safety protocols, and understanding your limits. Safe diving depends on careful dive planning, proper ascent techniques, and healthy lifestyle choices.

Proactive Dive Planning for Avoiding Decompression Sickness

Safe diving begins before you enter the water. Effective planning is your roadmap to safety.

- Use a Dive Computer: These devices track depth and time, calculating your no-decompression limits in real-time. Always follow their conservative guidance. If a computer fails, end the dive and stay out of the water for 24 hours.

- Understand Dive Tables: While computers are standard, knowing how to use dive tables makes you a safer diver. Always plan conservatively, for instance, by planning for a depth 10 feet deeper than your actual intended depth.

- Respect No-Decompression Limits (NDLs): NDLs are the maximum time you can spend at a given depth without needing mandatory decompression stops. Always stay well within these limits.

- Plan Repetitive Dives Correctly: Always perform your deepest dive first. This scientifically-backed practice minimizes nitrogen loading on subsequent, shallower dives.

- Take Adequate Surface Intervals: The longer you wait between dives, the more nitrogen your body eliminates. Give your body time to reset.

- Consider Enriched Air Nitrox (EANx): For certified divers, nitrox contains less nitrogen than air, reducing your nitrogen absorption. This extends bottom times and adds a significant safety buffer against DCS. More info about Decompression Science explains how gas mixtures affect nitrogen absorption.

Safe Ascent and Post-Dive Procedures

Your ascent is the most critical phase for avoiding decompression sickness.

- Control Your Ascent Rate: Never ascend faster than 30 feet per minute. Most modern computers recommend even slower rates. Follow your computer's guidance and breathe normally throughout your ascent.

- Perform Safety Stops: A safety stop at 15 feet for 3-5 minutes is mandatory, not optional. This pause allows for additional, safe off-gassing before you surface.

- Time Flying After Diving Carefully: Reduced aircraft cabin pressure can cause residual nitrogen to form bubbles. Follow established safety guidelines: wait at least 12 hours after a single no-decompression dive, 18 hours after multiple dives, and longer than 18 hours after any decompression dives.

- Avoid Hot Tubs and Saunas: Intense heat immediately after a dive can alter circulation and potentially accelerate bubble formation. Postpone the spa treatment.

Lifestyle Factors in Avoiding Decompression Sickness

Your overall health significantly impacts your diving safety.

- Stay Hydrated: Good hydration is critical for efficient circulation, which is necessary to transport nitrogen to the lungs for elimination. Drink plenty of water before, during, and after diving.

- Maintain Physical Fitness: A healthy weight and good cardiovascular fitness optimize your body's ability to handle nitrogen loads efficiently.

- Limit Alcohol: Alcohol contributes to dehydration and negatively affects circulation. Minimize its consumption during a dive trip.

- Get Adequate Rest: Fatigue impairs your body's ability to cope with diving stress. If you're tired, it's safest to skip a dive.

- Stay Warm: Cold temperatures can reduce circulatory efficiency. Dress appropriately for the conditions and warm up between dives.

Emergency Response, Treatment, and Further Learning

Despite the best planning for avoiding decompression sickness, emergencies can happen. A calm, decisive response is critical for a positive outcome.

What to Do If You Suspect DCS

If DCS symptoms appear, act immediately. Even mild symptoms require urgent attention.

- Administer 100% Oxygen: This is the most critical first aid step. It helps flush nitrogen from the body and supplies oxygen to tissues affected by bubbles. Continue oxygen until medical professionals take over.

- Contact Emergency Services: Immediately call local emergency services and a 24/7 diving emergency hotline. They can provide medical consultation and coordinate evacuation to a hyperbaric facility.

- Seek Medical Evaluation: Even if symptoms improve with oxygen, a full medical evaluation by a physician trained in diving medicine is essential.

- Do Not Attempt In-Water Recompression: This outdated practice is extremely dangerous and can worsen the situation or cause drowning. Recompression must only be done in a controlled medical chamber.

- Document the Dive: Provide medical teams with all dive profile information (depths, times, ascent rates). Monitor the diver's condition and report any changes.

For more guidance, Dr. Michael B. Strauss offers insights on pain-related diving problems.

Professional Treatment and Long-Term Outlook

Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy (HBOT) is the definitive treatment for DCS. In a recompression chamber, increased pressure shrinks nitrogen bubbles, while breathing 100% oxygen accelerates their elimination and promotes tissue healing. Treatment protocols vary based on severity, but promptness is key to a successful recovery.

The long-term outlook depends on the severity of the DCS and the timeliness of treatment. While many divers recover completely, delays can lead to lasting complications:

- Chronic Effects: These can include persistent joint pain, arthritis, or osteonecrosis (bone tissue death) in severe cases.

- Neurological Damage: Type II DCS can cause memory issues, poor coordination, numbness, or tingling.

Returning to diving after DCS requires clearance from a diving medicine specialist. A general guideline is to wait at least two weeks after pain-only DCS and six weeks or more after minor neurological symptoms. Severe cases may require permanent cessation from diving due to high recurrence risk.

Dr. Michael B. Strauss's work in Diving Science highlights the importance of continuous education. Understanding both prevention and emergency response is the best way to ensure a long and safe diving career.

For a comprehensive understanding of diving physiology and safety, purchase your copy of Diving Science Revisited today: https://www.bestpub.com/view-all-products/product/diving-science-revisited/category_pathway-48.html

DISCLAIMER: Articles are for "EDUCATIONAL PURPOSES ONLY", not to be considered advice or recommendations.