Understanding the Life-Saving Technique Every Diver Must Know

A controlled emergency ascent is a self-rescue technique for scuba divers to safely surface when out of breathing gas and unable to locate their buddy. The procedure involves swimming upward at a controlled rate while continuously exhaling to prevent lung overexpansion injuries.

Quick Answer: How to Perform a Controlled Emergency Ascent

- Look up toward the surface and confirm your situation

- Reach one hand above your head for protection from obstacles

- Swim upward using normal fin kicks at a controlled pace

- Exhale continuously making a steady "ahhh" sound throughout the ascent

- Maintain a safe ascent speed (no faster than 18m/60ft per minute)

- Keep your regulator in your mouth to potentially breathe expanding air

- Vent your BCD as needed to control buoyancy

- Establish positive buoyancy at the surface by orally inflating your BCD

Running out of air underwater, while preventable, remains a frequent trigger for diving emergencies. Poor air management, equipment malfunctions, or panic can lead to this dangerous situation. The Controlled Emergency Swimming Ascent (CESA) is a last-resort skill taught in open water courses. Performing it correctly can mean the difference between a safe surface and a diving fatality.

The CESA is complex because it demands calm decision-making under stress. You must manage buoyancy, control your ascent rate, and exhale continuously—all while your body is under duress. This guide breaks down the CESA into simple steps for any diver.

Quick controlled emergency ascent definitions:

The Complete Guide to Performing a Controlled Emergency Ascent

Nobody wants to find themselves out of air underwater. Yet knowing exactly how to execute a controlled emergency ascent could save your life. This isn't just another skill to check off during certification—it's a procedure that demands your complete understanding and respect.

Let's break down every phase of a CESA, from the moment you realize you're out of air to the moment you're safely breathing at the surface.

Pre-Ascent: The Decision and Initial Actions

The moment you realize you can't draw a breath is when your training is critical. First, confirm your out-of-air status by checking your submersible pressure gauge (SPG). If it reads empty, you must act. While this situation is often due to preventable issues like poor air management or equipment failure, your focus must be on a safe ascent.

Look for your buddy immediately. A quick scan of your surroundings is essential. If your buddy is close, an alternate air source ascent is your primary choice. You will ascend together, sharing their air supply.

If your buddy is not in sight or is too far to reach, the controlled emergency ascent is your self-rescue procedure.

Depth is a critical factor. CESA training is typically conducted in shallow water, 9 meters (30 feet) or less, for safety. However, in a real out-of-air emergency at greater depths without a buddy, a CESA is still your necessary course of action. The principle "bent is better than dead" applies; while risks increase with depth, ascending is imperative for survival. When you have no other options, the CESA is your lifeline.

The Ascent: Step-by-Step Execution of a Controlled Emergency Ascent

With the decision made, your training transforms into action. The procedure relies on Boyle's Law: as you ascend and pressure decreases, the air in your lungs expands.

Look up toward the surface to check for overhead obstacles and set a visual target.

Reach one arm straight up to protect your head, keeping your other hand on your BCD deflator.

Begin swimming upward with normal fin kicks at a controlled, steady pace.

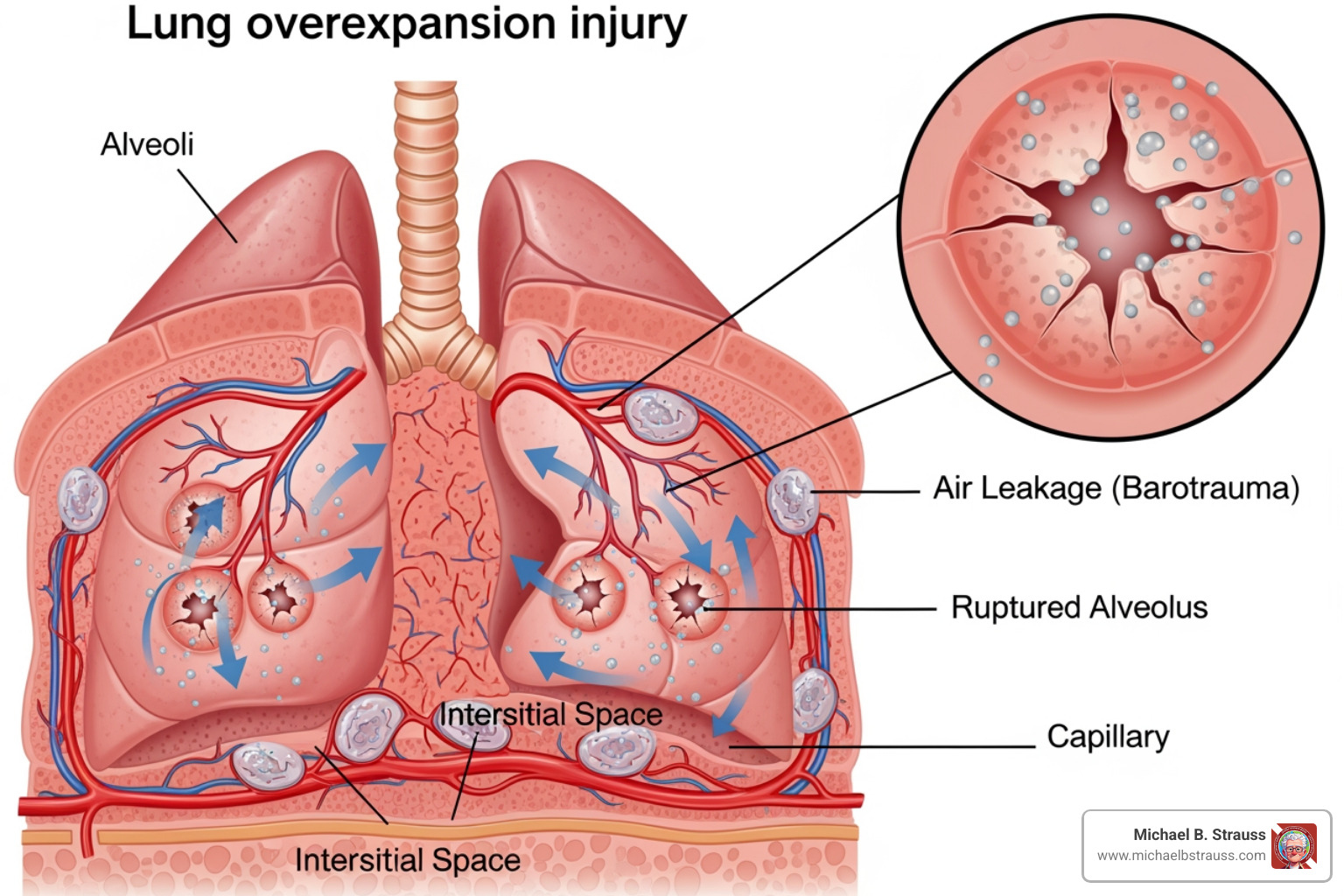

Exhale continuously by making a steady "ahhh" sound. This is the most critical step to prevent lung overexpansion injuries. Keep the regulator in your mouth to maintain an open airway.

Maintain a safe ascent speed of no more than 18 meters (60 feet) per minute. Resist the urge to rush.

Use your BCD deflator to manage buoyancy. As you rise, the air in your BCD will expand. Vent it in short bursts to prevent an uncontrolled ascent.

Each of these steps works together to transform a terrifying situation into a manageable emergency.

Reaching the Surface: Securing Your Safety

Breaking through the surface feels incredible, but your actions remain critical for safety.

Your first priority is to establish positive buoyancy. Immediately orally inflate your BCD until you can float effortlessly.

Dropping your weights should be a last resort. Dropping them during the ascent can cause an uncontrolled rocket to the surface, increasing injury risk. Drop your weights only if you cannot stay afloat after orally inflating your BCD.

Once you are buoyant, signal for help. Use your whistle, wave your arms, or deploy a surface marker buoy to attract attention from the boat or other divers.

Finally, rest, breathe, and monitor yourself for symptoms. The stress of the event is significant. Pay close attention to any signs of lung overexpansion or decompression sickness, such as chest pain, dizziness, or tingling. Seek immediate medical attention for any concerning symptoms, no matter how minor they seem. A successful CESA is a testament to your training, but it's also a critical learning experience to prevent future incidents.

Beyond the Ascent: Risks, Alternatives, and Advanced Knowledge

Successfully reaching the surface after a controlled emergency ascent is a tremendous relief, but understanding what could go wrong—and knowing your other options—is what separates a prepared diver from a lucky one. Let's explore the serious risks involved, how CESA compares to other emergency procedures, and why prevention and training matter so much.

Understanding the Risks of a Controlled Emergency Ascent

Even a correctly performed CESA carries significant risks due to rapid pressure changes.

- Lung Overexpansion Injuries (Pulmonary Barotrauma): This is the most immediate threat. If you fail to exhale continuously, expanding air can rupture lung tissue. This can lead to a collapsed lung (pneumothorax) or other serious conditions.

- Arterial Gas Embolism (AGE): The most dangerous form of barotrauma, AGE occurs when air bubbles enter the bloodstream and travel to the brain, causing stroke-like symptoms. Scientific research on pulmonary barotrauma in divers highlights that AGE is a leading cause of death in such incidents, underscoring the importance of constant exhalation.

- Decompression Sickness (DCS): A CESA is faster than a normal ascent and bypasses safety stops, increasing the risk of DCS. Nitrogen absorbed in tissues may not have time to off-gas safely. Learn more about Decompression Science.

- Drowning and Hypoxia: Loss of consciousness during the ascent or exhaustion at the surface can lead to drowning.

Poorly executed ascents can also have long-term consequences, including chronic lung issues or neurological damage. Understanding these risks reinforces the need for proper technique.

CESA and Other Emergency Ascent Techniques

Knowing your options in an out-of-air situation is key to making the right decision.

- Normal Ascent (Low-on-Air): The standard procedure when you notice you are low on air, but not yet out. You and your buddy ascend together in a controlled manner, completing a safety stop if air permits.

- Alternate Air Source Ascent: The preferred method when you are out of air and your buddy is nearby. You use your buddy's alternate air source and ascend together, maintaining control.

- Controlled Emergency Ascent (CESA): The self-rescue technique for when you are out of air and your buddy is not available. You maintain control by swimming and managing buoyancy.

- Buoyant Emergency Ascent: The absolute last resort, used when you cannot swim to the surface. It involves dropping weights for a rapid, uncontrolled ascent. While the risks of lung injury and DCS are extremely high, it is preferable to drowning.

- Buddy Breathing Ascent: This outdated technique, involving two divers sharing one regulator, is no longer taught in recreational diving due to its high risk and difficulty.

The main difference between a CESA and a buoyant ascent is control. A CESA is a controlled swim to the surface, while a buoyant ascent is an uncontrolled, rapid ride. A CESA is always the preferred self-rescue option if you are physically able to swim.

Training, Practice, and Prevention

Mastering the CESA begins with your certification but requires ongoing commitment.

Training and Practice: CESA is taught in a controlled, shallow-water environment with an instructor. However, skills diminish without use. Maintain proficiency through regular refresher courses, supervised pool practice, and even mental rehearsal before dives. This builds muscle memory and reduces the likelihood of panic.

Prevention is the Best Cure: As diving safety expert Dr. Michael B. Strauss emphasizes, most out-of-air emergencies are preventable.

- Pre-dive safety checks: Always confirm your tank valve is open, check your air pressure, and test all your equipment.

- Diligent air monitoring: Check your pressure gauge frequently throughout the dive and plan to surface with a safe reserve (at least 500 psi / 35 bar).

By deepening your knowledge of topics like Why and at What Sites Decompression Sickness Can Occur and exploring expert insights on Diving Science, you improve your decision-making and overall safety.

The goal is not to become an expert at emergency ascents, but to dive so conscientiously that you never need one. Prevention, preparation, and practice are the cornerstones of safe and enjoyable diving.

Get your copy of the book Diving Science Revisited here: https://www.bestpub.com/view-all-products/product/diving-science-revisited/category_pathway-48.html

DISCLAIMER: Articles are for "EDUCATIONAL PURPOSES ONLY", not to be considered advice or recommendations.