When Every Minute Counts: Understanding DCI Treatment

Decompression illness treatment requires immediate action and specialized medical care. If a diver shows symptoms after a dive, prompt response is critical to prevent permanent injury or death.

Immediate Actions for Suspected DCI:

- Administer 100% oxygen with a tight-fitting mask.

- Keep the person lying flat (supine position).

- Call emergency services and a specialized dive medicine hotline.

- Provide fluids (water or sports drinks) if conscious.

- Transport to a hyperbaric chamber for definitive recompression therapy.

The sooner treatment begins, the better the outcome. While most improvement occurs early in hyperbaric therapy, treatment can still be effective hours after symptoms appear.

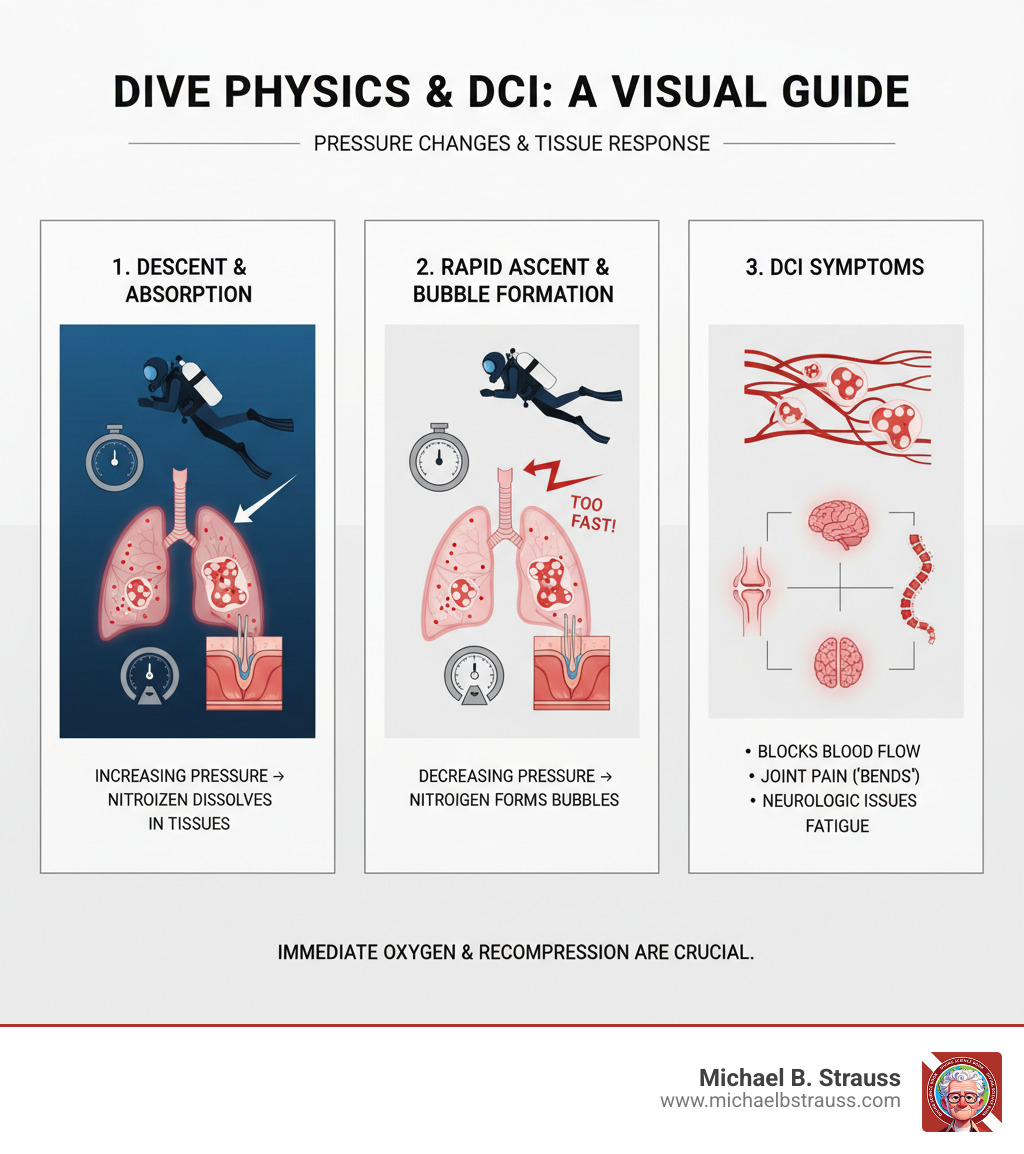

Decompression illness (DCI) occurs when dissolved gases (usually nitrogen) form bubbles in blood and tissues as pressure decreases. This can happen during ascent from a dive, rapid altitude changes, or even after a seemingly safe dive.

DCI includes two conditions: Decompression Sickness (DCS), where bubbles form in tissues, and Arterial Gas Embolism (AGE), where bubbles enter the arterial circulation from lung damage. Both require the same urgent treatment, though AGE symptoms are typically more sudden and severe, appearing within minutes of surfacing.

Related content about decompression illness treatment:

A Step-by-Step Guide to Decompression Illness Treatment

Knowing what to do when a diver shows signs of injury can mean the difference between full recovery and lasting damage. Decompression illness treatment begins with recognizing the signs.

Step 1: Recognizing the Signs and Making the Call

DCI symptoms can be deceptive. Only about half of those affected show symptoms within an hour of surfacing, and 90% within six hours. This delay can cause divers to dismiss warning signs as fatigue or muscle soreness.

Decompression Sickness (DCS) occurs when nitrogen bubbles form in tissues during ascent.

- Type I DCS affects the musculoskeletal system and skin, causing joint pain ("the bends"), itching, or a mottled skin rash. Though seemingly minor, it can lead to serious long-term issues like bone death if untreated.

- Type II DCS is more severe. Neurological DCS affects the brain or spinal cord, causing numbness, weakness, paralysis, or confusion. Inner ear DCS can cause vertigo and hearing loss, while pulmonary DCS ("the chokes") leads to chest pain and breathing difficulty.

Arterial Gas Embolism (AGE) is more dramatic, happening when gas bubbles enter the arterial bloodstream, often from a lung overexpansion injury. These bubbles can travel to the brain, causing sudden, stroke-like symptoms within minutes of surfacing, such as unconsciousness, paralysis, or convulsions.

| Symptom Category | Decompression Sickness (DCS) | Arterial Gas Embolism (AGE) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Cause | Bubbles forming in tissues from dissolved inert gas | Gas bubbles entering arterial circulation from lung overexpansion |

| Onset Time | Minutes to hours post-dive (50% within 1 hr, 90% by 6 hrs) | Sudden, within minutes of surfacing (often under 10 min) |

| Common Symptoms | Joint pain ("the bends"), skin rash/itching, unusual fatigue, numbness, tingling | Sudden unconsciousness, paralysis, convulsions, visual disturbances, confusion |

| Severe Symptoms | Weakness, paralysis, altered sensation, balance issues, "chokes" (chest pain, breathing difficulty), vertigo, hearing loss | Stroke-like symptoms, rapid collapse, severe neurological impairment, cardiac arrest |

| Affected Systems | Musculoskeletal, skin, lymphatic, neurological (brain, spinal cord, inner ear), cardiopulmonary | Neurological (brain, spinal cord), cardiovascular |

Fortunately, the immediate first aid for both DCS and AGE is identical. Your job is to recognize a problem and get help. Diagnosis depends on symptoms, the dive profile, and onset time. Since even subtle symptoms can indicate DCI, it's crucial to act.

When in doubt, make the call. Contact emergency medical services and a specialized dive medicine hotline. Be ready to provide the diver's location, symptoms, and dive details.

Step 2: Immediate First Aid for Suspected DCI

While waiting for transport, proper first aid can significantly improve the outcome.

- Administer 100% Oxygen: This is the most critical step. Use a tight-fitting non-rebreather mask at the highest flow rate (10-15 L/min). High-concentration oxygen helps shrink nitrogen bubbles, delivers oxygen to starved tissues, and reduces inflammation. Continue oxygen even if symptoms improve, as they can return.

- Keep the Person Lying Flat: Position the person on their back (supine). The outdated head-down position is not recommended as it can increase pressure in the brain.

- Provide Fluids: If the person is conscious and can swallow, offer water or sports drinks. Dehydration worsens DCI. Avoid alcohol and caffeine.

- Protect and Monitor: Keep the person warm and at rest. Continuously monitor their breathing, pulse, and consciousness. Be prepared to perform CPR if needed. If vomiting occurs, turn them on their side to clear their airway, then return them to a supine position.

These measures are a bridge to definitive care. For more details, see the evaluation and management of pain-related medical problems of diving and the consensus guideline on pre-hospital DCI management.

Step 3: The Gold Standard - Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy (HBOT)

The definitive decompression illness treatment is hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT), which directly addresses the gas bubbles.

How HBOT Works:Inside a pressurized chamber, the patient breathes 100% oxygen. This has three main effects:

- Reduces Bubble Size: Increased pressure physically compresses the gas bubbles (Boyle's Law), allowing blood flow to resume.

- Eliminates Nitrogen: Breathing pure oxygen creates a gradient that pulls nitrogen out of the bubbles and tissues to be exhaled.

- Oxygenates Tissues: High oxygen levels saturate the blood plasma, delivering oxygen to tissues even where circulation is blocked.

Treatment Protocol:The most common protocol is the U.S. Navy Treatment Table 6 (TT6), which involves breathing 100% oxygen at a pressure equivalent to 60 feet of seawater for nearly five hours, with scheduled air breaks to prevent oxygen toxicity. Most patients improve quickly, and many need only one session. The risk of oxygen toxicity seizures is very low (0.01%-0.05%).

Chamber Types:

- Monoplace chambers are clear tubes for a single patient, filled entirely with oxygen.

- Multiplace chambers are larger rooms pressurized with air, where multiple patients and medical staff can be inside. Patients breathe oxygen via masks or hoods, allowing for direct medical care.

For technical details, the U.S. Navy Diving Manual on recompression therapy is the authoritative guide.

Beyond the Chamber: Recovery, Prevention, and Future Dives

Recovery from DCI extends beyond the hyperbaric chamber and involves understanding adjunctive therapies, long-term effects, and how to prevent a recurrence.

Adjunctive Therapies and Factors Affecting Recovery

While HBOT is the primary decompression illness treatment, other factors influence recovery. The sooner treatment begins, the better the outcome, but significant improvement is still possible even with delayed treatment. Never give up on seeking care.

Supportive treatments include:

- Intravenous fluids to combat dehydration and improve circulation.

- NSAIDs for pain management, if medically appropriate.

- Low molecular weight heparin or compression devices to prevent blood clots in cases of neurological DCI with leg weakness.

Corticosteroids and lidocaine are not routinely recommended based on current evidence. For more information, see these resources on Decompression Science and UHMS guidelines on adjunctive therapies.

A Note on In-Water Recompression (IWR):IWR, or taking a diver back underwater, is extremely dangerous and not endorsed for routine use. It should only be considered as a last resort in remote locations where a hyperbaric chamber is many hours or days away. The risks of drowning, oxygen toxicity seizures, and hypothermia are substantial. Surface first aid and transport are almost always the safer option.

Long-Term Consequences and Returning to Diving

Most people who receive prompt treatment recover completely. However, some may experience lasting effects, such as residual neurological deficits (numbness, weakness, balance issues), chronic pain, or dysbaric osteonecrosis (bone death). This condition, which affects joints like the shoulder and hip, can develop months or years after a DCI incident, particularly if initial joint pain was untreated. Learn more about Why and at What Sites Decompression Sickness Can Occur.

Making the Return-to-Diving Decision:Consulting a dive medicine physician is mandatory before diving again. General guidelines are:

- Pain-only DCI (fully resolved): Wait a minimum of two weeks.

- Minor neurological DCI (fully resolved): Wait at least six weeks.

- Severe neurological DCI or any persistent symptoms: Do not return to diving.

A thorough medical evaluation is essential, especially if DCI occurred despite following safe dive profiles, as it may indicate an underlying condition like a Patent Foramen Ovale (PFO).

Prevention and Special Considerations

Prevention is always better than treatment. Reduce your DCI risk by following safe diving practices.

Key Prevention Strategies:

- Dive Conservatively: Limit depth and bottom time, staying well within the limits of your dive computer or tables.

- Ascend Slowly: Follow recommended ascent rates (no faster than 30 feet/minute) and perform a 3-5 minute safety stop at 15 feet.

- Stay Hydrated: Drink plenty of water before and after diving. Avoid alcohol.

- Plan Surface Intervals: Allow adequate time between dives for nitrogen to off-gas.

- Avoid Flying Too Soon: Wait at least 12 hours after a single no-decompression dive, 18 hours after multiple dives, and 24-48 hours after decompression dives before flying or going to altitude. If you have any symptoms, seek medical evaluation before flying.

Pre-Dive Health:Be aware of how health conditions like heart or lung disease, diabetes, or a Patent Foramen Ovale (PFO) can increase DCI risk. Healthcare professionals can help assess fitness to dive. Dr. Michael B. Strauss's books offer expert guidance on diving safety. Learn more about the science of diving safety.

To dive deeper into the science of safe diving, get your copy of Diving Science Revisited here.

DISCLAIMER: Articles are for "EDUCATIONAL PURPOSES ONLY", not to be considered advice or recommendations.