Why Understanding Decompression Sickness Symptoms Could Save a Life

Decompression sickness symptoms can appear suddenly, even after dives that seemed completely safe. In fact, one-third of divers who develop decompression sickness (DCS) were within their dive table limits when symptoms struck.

Quick Reference: Key Decompression Sickness Symptoms

| Type I DCS (Less Severe) | Type II DCS (More Severe) |

|---|---|

| Joint pain ("the bends") - 60-70% of cases | Numbness or weakness in limbs |

| Skin rash or itching - 10-15% of cases | Confusion or altered mental state |

| Fatigue and malaise | Paralysis or loss of coordination |

| Muscle aches | Difficulty breathing ("the chokes") |

| Vertigo or hearing loss |

The name "the bends" comes from the way affected divers bend over in pain when nitrogen bubbles form in their major joints. But joint pain is just one piece of the puzzle.

When symptoms appear matters too:

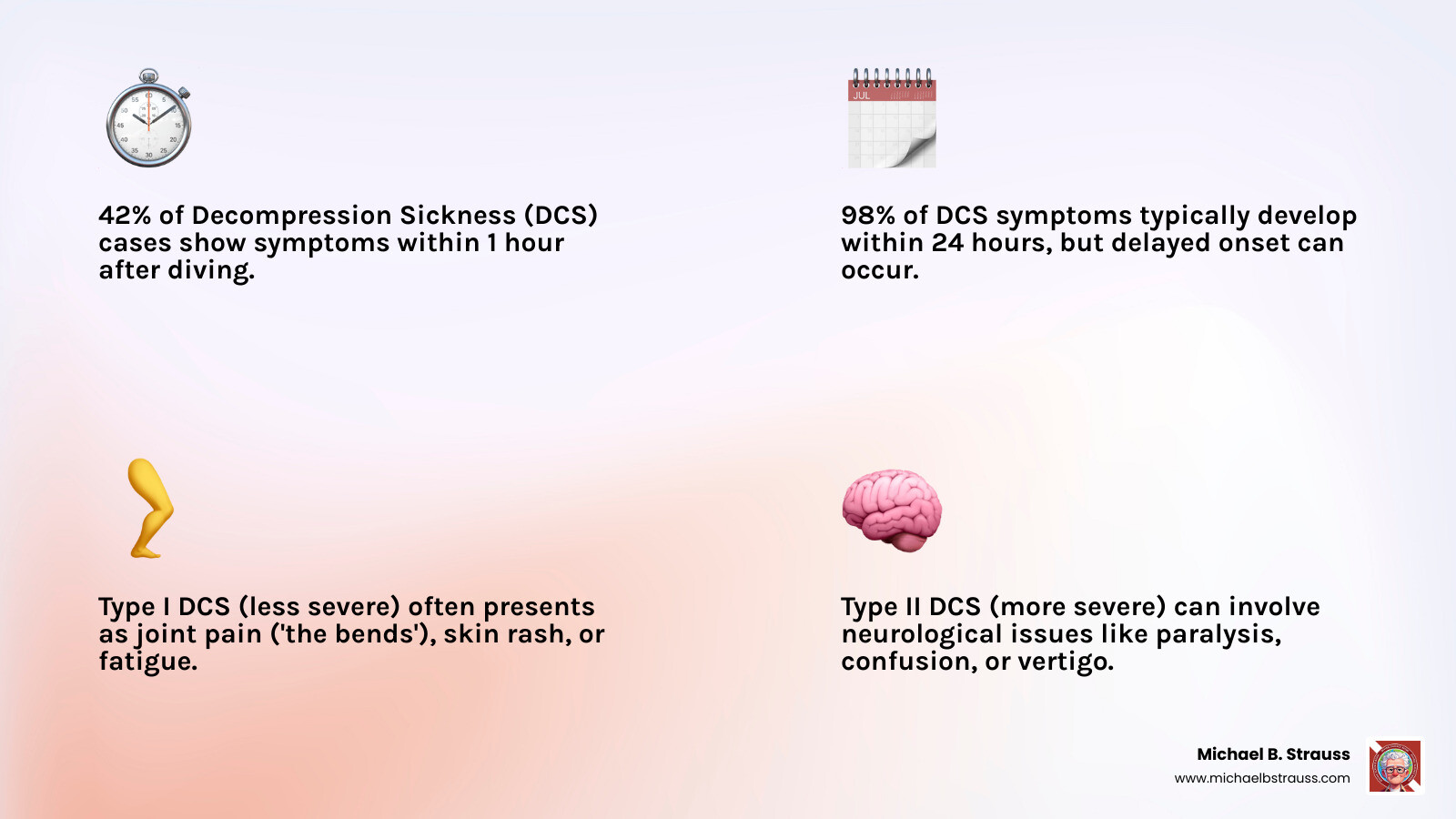

- 42% of cases show symptoms within 1 hour

- 98% develop symptoms within 24 hours

- Delayed symptoms can occur, especially after flying

As first demonstrated in 1670, rapid pressure changes cause dissolved gases to form bubbles—much like opening a carbonated drink. In divers, these nitrogen bubbles can damage tissues, block blood flow, and trigger serious complications.

The tricky part is that these symptoms often mimic other conditions like muscle strains, the flu, or even a stroke. That's why any unusual symptom within 48 hours after diving should be treated as potential DCS until proven otherwise.

The Telltale Signs: A Comprehensive Guide to Decompression Sickness Symptoms

You've just completed what felt like a perfect dive, but an hour later, a nagging pain appears in your shoulder. Could this be decompression sickness symptoms? Understanding what's happening in your body is key to a quick recovery. For a concise overview of the condition, see Decompression sickness.

What Causes Decompression Sickness?

Decompression Illness (DCI) is an umbrella term for two conditions. Decompression Sickness (DCS), or "the bends," is caused by nitrogen bubbles forming in tissues during ascent. Arterial Gas Embolism (AGE) is more severe and occurs when expanding air ruptures lung tissue, sending gas bubbles into the bloodstream, often to the brain.

Following Henry's law, your body tissues absorb more nitrogen from the air you breathe the deeper you dive. If you ascend too quickly, this dissolved nitrogen doesn't have time to be exhaled and instead forms bubbles inside your body—much like opening a shaken soda bottle. These bubbles can distort tissues, block blood flow, and trigger a cascade of problems.

While primarily a diving concern, DCS can also affect caisson workers, astronauts, and aviators in unpressurized aircraft. For a deeper understanding of how pressure affects your body, Decompression Science offers excellent insights.

Common Decompression Sickness Symptoms: From Mild to Severe

Type I DCS primarily involves joint pain and skin issues. Joint pain is the most common symptom (60-70% of cases), presenting as a deep, aching feeling not typically worsened by movement. Shoulders are most commonly affected. Skin problems (10-15% of cases) include itching, a blotchy rash, or a marbled appearance called cutis marmorata. Vague constitutional symptoms like unusual fatigue, headache, and nausea are also common and can be mistaken for the flu.

Type II DCS is a medical emergency involving the nervous, inner ear, or cardiopulmonary systems. Neurological symptoms are the most concerning, including numbness, muscle weakness, coordination problems, confusion, or paralysis. Inner ear DCS ("the staggers") causes severe vertigo, ringing in the ears (tinnitus), and hearing loss. Cardiopulmonary DCS ("the chokes") is rare but involves a dry cough, chest pain, and severe difficulty breathing.

| Type I DCS (Less Severe) | Type II DCS (More Severe) |

|---|---|

| Joint pain ("the bends") - 60-70% of cases | Numbness or weakness in limbs |

| Skin rash or itching - 10-15% of cases | Confusion or altered mental state |

| Fatigue and malaise | Paralysis or loss of coordination |

| Muscle aches | Difficulty breathing ("the chokes") |

| Vertigo or hearing loss |

Why and at What Sites Decompression Sickness Can Occur provides valuable context for these varied manifestations.

When Do Symptoms Appear and What Can They Mimic?

Symptoms don't always appear immediately. While 42% of people develop symptoms within 1 hour, 98% show them within 24 hours. This delayed onset often leads to misdiagnosis, as divers may not connect their symptoms to a recent dive.

The challenge is that decompression sickness symptoms can mimic many other conditions, such as:

- Muscle strains

- Flu-like symptoms

- Dehydration

- Stroke or migraine

- Motion sickness or food poisoning

This is why the golden rule in dive medicine is: any unusual symptom within 48 hours of diving should be treated as potential DCS until proven otherwise.

Recognizing Serious Neurological Decompression Sickness Symptoms

When decompression sickness symptoms affect the nervous system, it is a medical emergency. Your brain and spinal cord are vulnerable to bubble formation and damage.

Spinal cord involvement can cause motor weakness, paralysis, numbness, tingling, loss of bladder or bowel control, and a "girdle" pain that wraps around the torso.

Brain symptoms can mimic a stroke and include confusion, visual disturbances (blurred or double vision), speech difficulties, poor coordination, and dizziness.

Inner ear DCS creates severe vertigo, intense nausea, tinnitus (ringing in the ears), and hearing loss, which can be permanent if not treated quickly.

Cardiopulmonary DCS is rare but dangerous, causing a dry cough, deep chest pain, and severe difficulty breathing.

Any of these serious symptoms constitutes a medical emergency. The sooner a person receives recompression therapy, the better their chance of a full recovery. For comprehensive insights, Dr. Michael B. Strauss offers extensive resources at Michael B. Strauss's website.

Next Steps: From First Aid to Future Dives

When decompression sickness symptoms strike, knowing what to do can make the difference between a full recovery and lasting complications. With proper first aid and prompt medical attention, most divers recover fully.

First Aid and Diagnosis on the Spot

The moment you suspect DCI, every action counts. These first aid steps are essential but are not a substitute for professional medical care.

Immediately contact emergency services and the Divers Alert Network (DAN). Provide the diver's symptoms and dive profile. While waiting for help, follow these steps:

- Administer 100% Oxygen: This is the most important step. Use a tight-fitting non-rebreather mask to provide the highest concentration of oxygen possible. This helps shrink nitrogen bubbles and flush excess nitrogen from the body. The diver still needs a medical evaluation even if symptoms improve.

- Position the Diver: Have the diver lie flat on their back to maintain blood flow to the brain. If they are unconscious or vomiting, use the recovery position.

- Hydrate: If the diver is conscious, encourage them to sip non-alcoholic fluids like water.

- Keep Warm: Use blankets to prevent hypothermia.

- Document Details: Note the dive profile (depths, times, ascent rate) and when symptoms started.

Avoid giving painkillers unless advised by a medical professional, as they can mask symptoms. Never give aspirin.

Dr. Michael B. Strauss's expertise in the Evaluation and Management of Pain-Related Medical Problems of Diving provides deeper insights into managing these situations.

Professional Treatment and Long-Term Recovery

The definitive treatment for DCI is Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy (HBOT). This involves taking the diver back "underwater" in a controlled medical chamber to breathe pure oxygen under pressure.

HBOT works by using increased pressure to shrink nitrogen bubbles while 100% oxygen accelerates nitrogen elimination and delivers oxygen to injured tissues. Most divers respond well, but those with neurological symptoms may need multiple sessions.

Understanding your risk factors is key to prevention:

- Physiological: Patent Foramen Ovale (PFO), age, high body fat, dehydration, fatigue.

- Dive-Related: Cold water, deep or long dives, rapid ascents, repetitive dives.

Prevention is always better than cure. Follow these guidelines:

- Plan dives conservatively and use a dive computer.

- Maintain slow, controlled ascent rates and perform safety stops.

- Stay well-hydrated and allow for adequate surface intervals.

- Avoid strenuous exercise, alcohol, and flying immediately after diving.

While the outlook is generally excellent with prompt treatment, some complications like dysbaric osteonecrosis (bone tissue death) or persistent neurological deficits can occur. Returning to diving after DCI requires careful medical evaluation and clearance. Severe cases may mean retiring from diving to prioritize long-term health.

The comprehensive resources available through Diving Science provide invaluable guidance for navigating these complex decisions.

To learn more, get your copy of Diving Science, Revisited here: https://www.bestpub.com/view-all-products/product/diving-science-revisited/category_pathway-48.html

DISCLAIMER: Articles are for "EDUCATIONAL PURPOSES ONLY", not to be considered advice or recommendations.