Why Dive Accident Management is Every Diver's Responsibility

Dive accident management is a systematic approach to handling diving emergencies that every serious diver should master. Understanding how to prevent, recognize, and respond can mean the difference between a minor incident and a life-threatening emergency.

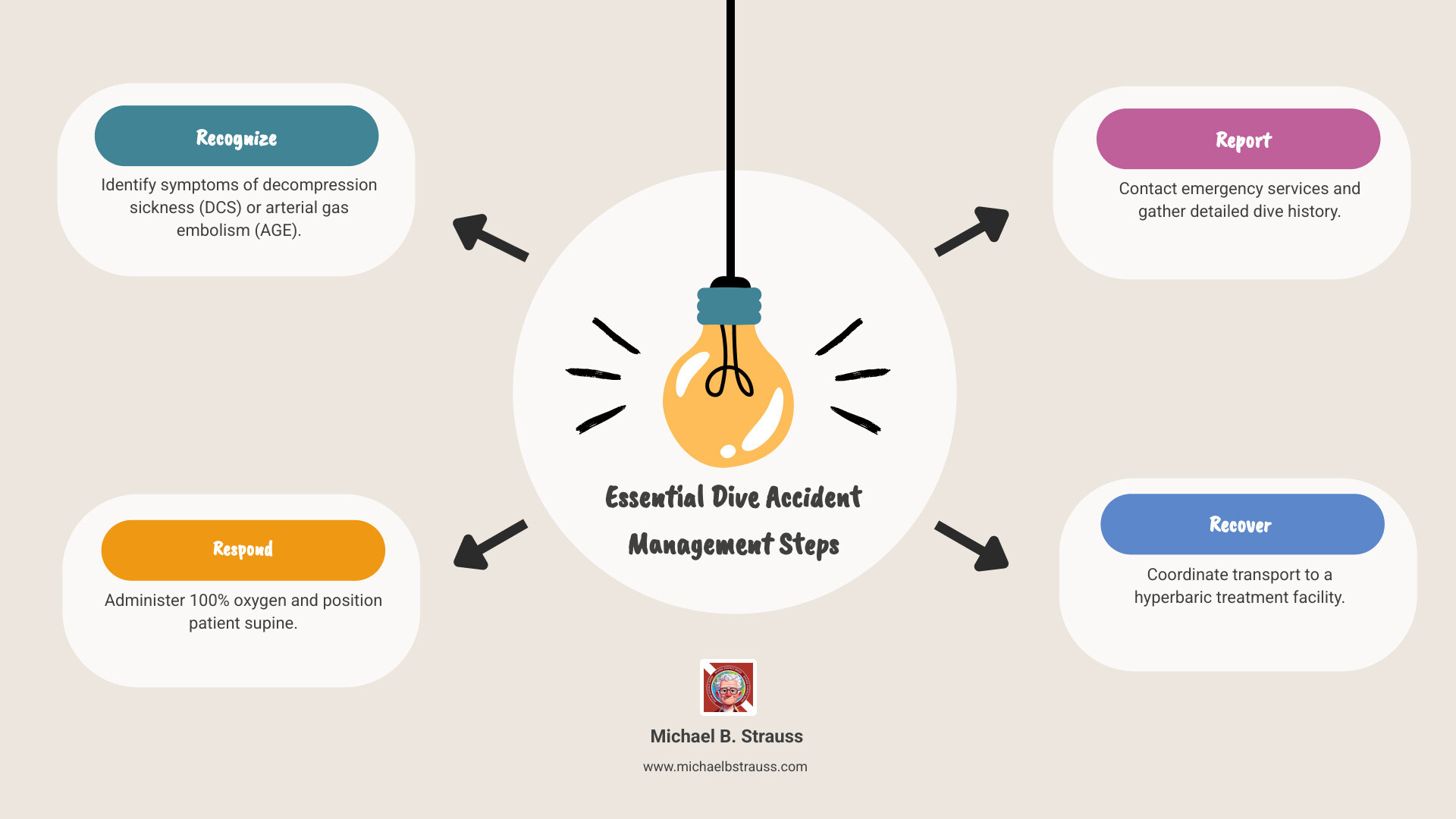

Essential Dive Accident Management Steps:

- Recognize - Identify symptoms of decompression sickness (DCS) or arterial gas embolism (AGE).

- Respond - Administer 100% oxygen and position the patient correctly.

- Report - Contact emergency services and provide a detailed dive history.

- Recover - Coordinate transport to a hyperbaric treatment facility.

The most serious diving injuries, decompression sickness and arterial gas embolism, relate to how pressurized gas behaves underwater. DCS involves nitrogen bubbles forming in tissues during ascent, while AGE occurs when lung over-expansion forces air into the bloodstream. Arterial gas embolism is the most common cause of death in scuba diving, but with proper knowledge, most diving accidents are preventable or manageable.

Dive accident management is a comprehensive safety system, from prevention and immediate response to proper follow-up care. Every step matters.

Dive accident management terms made easy:

The Complete Guide to Dive Accident Management

A thrilling scuba diving trip relies on prioritizing safety. True mastery of diving isn't just about buoyancy or navigation; it's about confidently handling the unexpected. This guide covers the essentials of dive accident management to turn you from a bystander into a capable responder.

Recognizing the Enemy: DCI (DCS & AGE)

The most critical dive injuries are Decompression Sickness (DCS) and Arterial Gas Embolism (AGE), often grouped as Decompression Illness (DCI). They are caused by how gases behave under pressure.

Decompression Sickness (DCS) occurs when dissolved nitrogen forms bubbles in tissues or the bloodstream during ascent. It's often called "the bends." Risk factors include deep or long dives, rapid ascents, dehydration, and cold water.

- Type 1 DCS: Considered milder, with symptoms like joint pain and skin rashes.

- Type 2 DCS: More serious, affecting the nervous, cardiovascular, or respiratory systems. Symptoms include headache, dizziness, nausea, weakness, and loss of coordination.

Arterial Gas Embolism (AGE) is caused by lung over-expansion during a rapid or breath-hold ascent. This forces gas into the bloodstream, where it can travel to the brain. AGE is the most common cause of death in diving. Symptoms are sudden and severe, appearing within 10 minutes of surfacing, and can include collapse, loss of consciousness, seizures, and paralysis.

While differentiating between DCS and AGE can be difficult, the initial on-site treatment is the same.

| Condition | Symptoms | Onset Time | Cause |

|---|---|---|---|

| DCS (Type 1) | Joint pain, skin rash, urticaria (hives). Can be fleeting or increase over time. | Minutes to hours | Nitrogen absorbed during a dive forms bubbles in tissues (blood, lymphatic system) when pressure decreases too rapidly during ascent. |

| DCS (Type 2) | Headache, blurred vision, nausea, dizziness, ataxia, shortness of breath, hypotension, weakness, paralysis, confusion. Involves central nervous, cardiovascular, respiratory systems. | Minutes to hours | More severe bubble formation affecting vital systems. |

| AGE | Sudden collapse, unconsciousness, seizures, visual disturbances, weakness, paralysis, disorientation, bloody sputum, chest pain, shortness of breath. Primarily neurological. | Immediate to 10 minutes | Pressurized gas expands during ascent, rupturing lung alveoli and introducing air into the bloodstream, which then travels to arterial circulation, potentially blocking blood flow to vital organs, especially the brain. Often caused by breath-holding on ascent. |

More info about Decompression Science

The First 15 Minutes: Immediate On-Site Actions

Your actions in the first 15 minutes are critical. The goal is to stabilize the diver and prepare them for advanced medical care.

- Assess the Diver: Ensure the scene is safe, then check if the diver is conscious and breathing.

- Administer 100% Oxygen: This is the single most important action. Use a non-rebreather mask at a flow rate of 10-15 liters per minute. Oxygen helps shrink gas bubbles and flush nitrogen from the system.

- Position the Patient: Lay the diver flat on their back (supine). If they are unconscious, place them in the recovery position on their left side.

- Maintain Body Temperature: Protect the diver from the elements with blankets to prevent hypothermia.

- Contact Emergency Services (EMS): Call for help immediately. Provide your location, the nature of the emergency, and the diver's condition.

Learn about Oxygen Administration

More info about pain management in diving

Critical Steps in Dive Accident Management

After providing first aid, your role shifts to gathering information for medical professionals.

1. Collect a Detailed Dive History:

- Maximum depth and bottom time?

- Gases used?

- Ascent rate (controlled, uncontrolled, rapid)?

- Safety stops performed?

- When did symptoms begin?

- What are the specific symptoms?

- Any previous medical issues?

- Was strenuous activity performed during or after the dive?

2. Interview the Dive Buddy: The buddy can provide crucial details about the dive and the diver's behavior.

3. Secure the Dive Computer: The dive computer contains invaluable data like depth, time, and ascent rates. This objective information is vital for the hyperbaric medical team.

4. Document Everything: Keep a written record of times, symptoms, and actions taken to create a clear timeline for medical staff.

More info on where DCS can occur

The Path to Recovery: Referral and Hyperbaric Treatment

Getting the diver to definitive care is the next step. For DCI, this means a hyperbaric chamber.

1. Activate EMS and Specialized Consultation: After calling EMS, contact a specialized dive medical service. Many organizations offer 24/7 emergency hotlines with diving medical experts who can provide guidance and coordinate care.

2. Recompression Therapy: The definitive treatment for DCS and AGE is recompression in a hyperbaric chamber. This re-pressurizes the diver, shrinking bubbles and improving oxygen delivery to tissues. Treatment should be sought as soon as possible.

3. Transport Considerations: If air transport is needed, the cabin altitude must be kept as low as possible (ideally below 300 meters / 1,000 feet) to prevent the diver's condition from worsening. Always notify the hyperbaric facility before arrival.

4. Specialized Insurance: Standard health insurance may not cover the high costs of hyperbaric treatment and medical evacuation. Specialized dive accident insurance is strongly recommended.

Direct Transport To Hyperbaric Facility

Prevention is the Best Cure: Proactive Dive Safety

The best way to manage a dive accident is to prevent it.

- Plan Carefully: Assess your capabilities, environmental conditions, and dive profile. Always have a contingency plan.

- Stay Fit and Hydrated: Good physical condition is key. Avoid alcohol before diving and stay hydrated.

- Maintain Your Gear: Perform pre-dive checks on all equipment and have it serviced regularly.

- Have Emergency Equipment Ready: Every dive operation should have a well-stocked first-aid kit, communication devices, and, most importantly, an emergency oxygen kit.

- Refresh Your Skills: Practice emergency procedures and rescue skills regularly to stay sharp.

By embracing proactive safety, you minimize risks and contribute to a safer diving environment for everyone.

Conclusion: Becoming a Prepared Diver

Mastering dive accident management is about weaving preparedness into every dive. It's a continuous journey of thinking ahead, staying ready, and never stop learning. From recognizing DCI to coordinating hyperbaric treatment, every step is part of a safety-first mindset.

A prepared diver has a practical Emergency Action Plan (EAP) custom to their specific dive locations. This plan outlines who to call, what to do, and where emergency equipment is located. But a plan is only useful if it's practiced. Regularly run drills with your dive buddies to ensure your response is automatic in a real crisis.

This culture of preparedness extends to understanding the realities of dive safety. For dive professionals, proper procedures and insurance are non-negotiable. For all divers, continuous education is what separates the good from the great. Our knowledge needs constant refreshing, as new research emerges and skills can get rusty.

Dr. Michael B. Strauss's books are invaluable resources for this journey, offering practical guides that deepen your understanding of diving physiology and emergency response. They are essential for any diver committed to safety.

Excellent dive accident management is about fostering a community-wide culture of safety. When we share knowledge, practice skills, and prioritize safety over convenience, we protect ourselves and our fellow divers, ensuring everyone can enjoy the underwater world with confidence.

Explore more diving safety resources

To deepen your knowledge, get your copy of 'Diving Science Revisited' today.

DISCLAIMER: Articles are for "EDUCATIONAL PURPOSES ONLY", not to be considered advice or recommendations.