Why Diving Health and Safety Matters More Than You Think

Diving health and safety is the comprehensive approach to preventing accidents and managing risks underwater. Understanding these principles is crucial for any diver, as it can mean the difference between an amazing dive and a life-threatening emergency.

Key Areas of Diving Health and Safety:

- Medical fitness - Ensuring your body can handle the physiological demands of diving

- Equipment safety - Proper maintenance and pre-dive checks of life-support systems

- Environmental awareness - Understanding conditions like currents, visibility, and contaminated water

- Emergency preparedness - Recognizing symptoms and responding to diving-related injuries

- Risk management - Following established procedures and diving within your limits

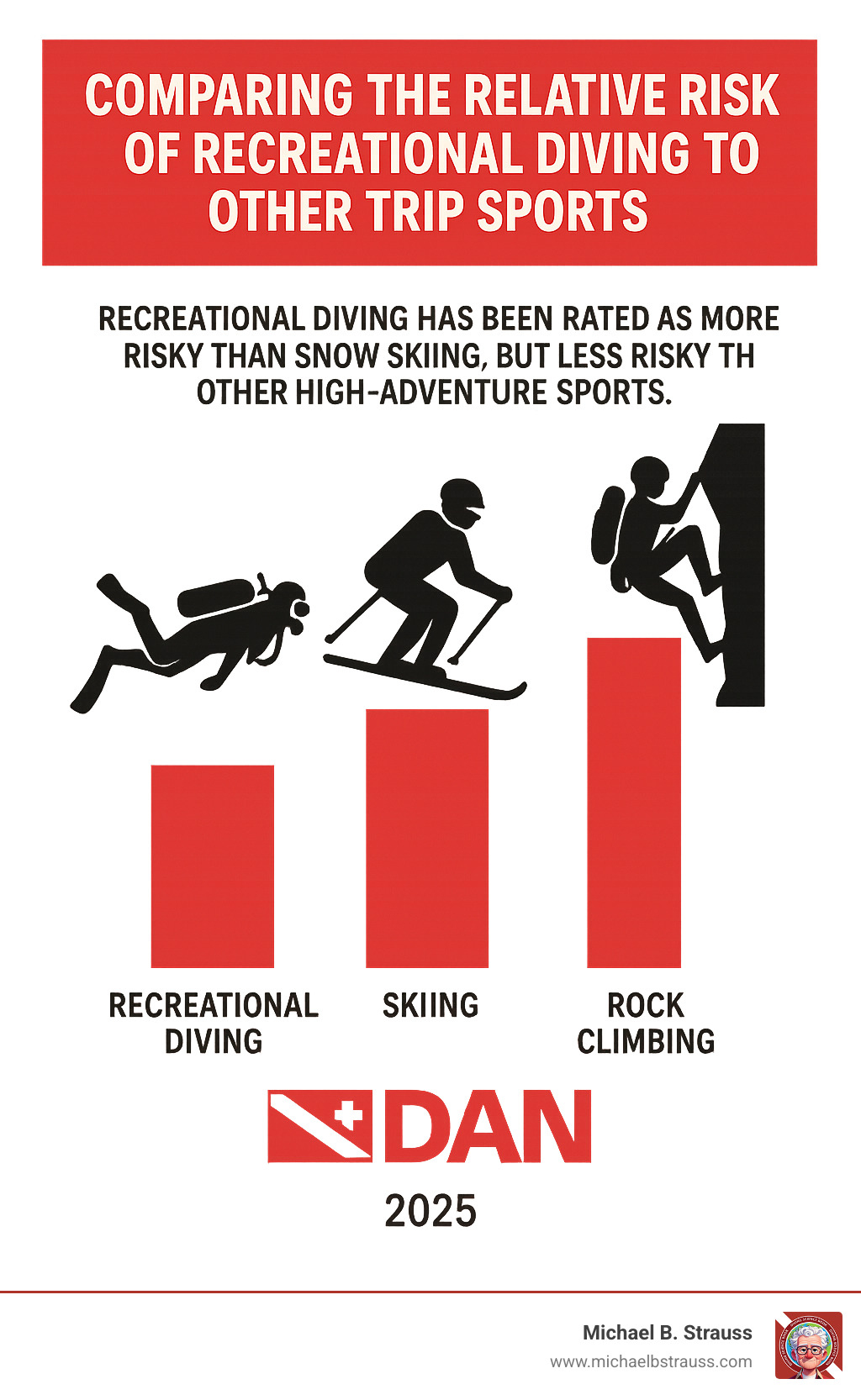

Statistics show that human error causes 60% to 80% of all diving accidents. Most severe injuries happen to new divers or those who push beyond their training. However, with proper knowledge and preparation, diving has a good safety record compared to other trip sports.

As one diving safety expert puts it, "Safety is not the absence of accidents. Safety is the presence of defenses." This means building layers of protection through training, equipment checks, dive planning, and emergency procedures. The underwater environment presents unique physiological challenges, affecting everything from your cardiovascular system to your ears and lungs. Understanding and managing these effects is essential for safe diving.

Introduction to Diving Safety

Picture yourself floating weightlessly in crystal-clear water, surrounded by colorful fish. That magical moment is possible when safety comes first. Diving health and safety isn't a boring checklist; it's your ticket to countless incredible underwater trips.

Diving is an trip sport with inherent risks. However, recreational diving is generally considered safer than activities like rock climbing or motorcycle racing. The key takeaway is that most diving accidents are preventable, often stemming from simple mistakes that proper training and awareness can eliminate. Most serious incidents happen to newer divers or those pushing beyond their training limits, so respect your boundaries and continue learning.

It's also important to be mentally prepared. Over half of all divers have experienced panic underwater at some point, with 65% of recreational divers admitting to it. Understanding why panic occurs and how to manage it is a crucial part of diving health and safety.

Diving safety isn't about eliminating fun; it's about maximizing it. When you understand and manage the risks, you can dive with confidence. Studies show that very few diving fatalities (only 4.46%) are caused by a single factor. Most incidents involve multiple things going wrong. This highlights the importance of good safety practices, which create layers of protection. Proper planning, equipment checks, and staying within your limits build a strong safety net, allowing you to enjoy diving to the fullest.

Mastering Proactive Diving Health and Safety

Our journey towards safer diving begins long before we ever enter the water. Proactive measures, from ensuring our physical and mental readiness to carefully planning our dives and checking our gear, are the cornerstones of responsible diving.

Medical Fitness: Are You Cleared to Dive?

Your body is your most important piece of diving equipment, so ensuring your medical fitness is the first step in diving health and safety. Be honest about your health, and if you have any concerns or pre-existing conditions, consult a healthcare professional, preferably one trained in diving medicine.

Ask your doctor these crucial questions:

- What health conditions might prevent me from scuba diving?

- Are my medications safe to take while diving?

- How might diving affect my health, given my medical history?

Cardiovascular conditions are a major concern, linked to 25-33% of scuba fatalities. Regular medical evaluations are especially important for divers over 45. Psychological fitness is also vital. Over half of all divers have experienced panic underwater. If you feel stressed, remember to Stop, Breathe, Think, Act to regain control. Finally, don't forget that proper hydration is crucial for preventing medical problems. For more details, explore Scientific research on scuba diving safety and get More info about diving science.

Essential Dive Planning and Equipment Checks

Thorough dive planning and equipment checks are non-negotiable for diving health and safety. Always remember: "Plan your dive, and dive your plan." Before entering the water, you and your buddy must agree on the maximum depth, bottom time, and ascent plan.

The Buddy System: Never dive alone. Your buddy is a key safety component. Ensure you are compatible in experience and perform a buddy check before every dive.

Environmental Factors: Pay close attention to tides, weather, currents, and visibility. Be prepared to cancel a dive if conditions are unfavorable.

Equipment Maintenance: Your gear is your lifeline. Regularly inspect and service all equipment, including regulators, gauges, and BCDs. Ensure your breathing air is high quality and that gear used for enriched air nitrox (over 40% oxygen) is properly cleaned for oxygen service.

Pre-Dive Checklists: Use a checklist to reduce human error. A common mnemonic is BWRAF (or a similar one from your training agency):

- BCD/Buoyancy: Check inflation/deflation.

- Weights: Confirm proper amount and secure release.

- Air: Check pressure, taste, and ensure it's on.

- Personal Gear: Mask, fins, computer, etc.

- Releases: Know how to operate all releases on your and your buddy's gear.

For commercial diving, specialized checklists like the Delta-P Diving Checklist manage specific hazards. Treat every dive with the same level of caution.

Understanding Key Diving Hazards

Awareness of underwater hazards is a core tenet of diving health and safety. Understanding these risks is the first step toward mitigating them.

Decompression Sickness (DCS): Known as "the bends," this is caused by ascending too quickly. Avoid it by following your dive computer, ascending slowly, and performing safety stops. Learn more with this More info on Decompression Science.

Barotrauma: Tissue damage from pressure changes. This includes middle ear "squeezes" (the most common diving medical issue) and severe lung overexpansion injuries (pulmonary barotrauma), which can result from holding your breath on ascent.

Nitrogen Narcosis: A reversible, anesthetic effect of nitrogen at depth that can impair judgment. Its effects lessen as you ascend to shallower depths.

Oxygen Toxicity: A risk when using enriched air nitrox or mixed gases, caused by high partial pressures of oxygen. It can affect the central nervous system or lungs.

Drowning: The final outcome of an uncontrolled underwater event, often resulting from other issues like equipment failure or incapacitation.

Hypothermia: A dangerous drop in body temperature from prolonged exposure to cold water. Always use appropriate thermal protection.

Delta-P (Differential Pressure): A critical hazard near underwater structures like pipes or dams. The powerful suction created by water moving through an opening can be fatal. See the OSHA Alert on Delta-P for more.

Contaminated Water: A significant risk for commercial and scientific divers, requiring special protocols and equipment.

Commercial divers also face underwater construction hazards like cutting and welding. Understanding all potential hazards allows for proper planning and control measures to ensure safety.

In-Water Procedures and Emergency Response

The moment we slip beneath the surface, everything changes. Our carefully laid plans now meet reality, and our diving health and safety depends on how well we execute the procedures we've learned. Think of it this way: all that preparation was like studying for a test - now we're taking it, and the stakes couldn't be higher.

Best Practices for In-Water Diving Health and Safety

Once underwater, your diving health and safety depends on executing proper procedures. With the right techniques, you can steer the underwater world safely and confidently.

Buoyancy Control is key to gliding effortlessly, conserving air, and protecting the marine environment. Poor control leads to rapid air consumption and potential damage to yourself or the reef.

A Slow Ascent Rate is crucial. Ascend slower than 30 feet per minute. Your dive computer will warn you if you're going too fast; do not ignore it.

Safety Stops are your best defense against decompression sickness. A three-minute stop at 15 feet allows your body to safely off-gas nitrogen.

Air Supply Management means checking your air gauge frequently. A common practice is the "rule of thirds": one-third of your air for the journey out, one-third for the return, and one-third in reserve.

Never Hold Your Breath is the cardinal rule of diving. Always breathe continuously to avoid lung-overexpansion injuries during ascent.

Situational Awareness means staying aware of your depth, time, air supply, location, and your buddy's status. The underwater environment is dynamic, so stay alert.

Manage Problems Calmly by resisting the urge to panic if something unexpected happens. Stop, Breathe, Think, Act. This simple process can prevent minor issues from becoming major emergencies.

Recognizing and Responding to Diving Emergencies

Recognizing problems early and responding correctly can be lifesaving. Knowing the signs of major diving injuries is critical.

Symptoms of decompression sickness (DCS) can include joint pain, numbness, or a skin rash. Arterial gas embolism (AGE) is often more sudden, with symptoms like weakness, confusion, or unconsciousness immediately after surfacing. If you suspect either, seek medical help immediately.

Administering 100% oxygen is the standard first aid for serious diving injuries and can be crucial while awaiting professional medical care. Know how to use the oxygen kit on your dive boat.

Before you dive, always know the emergency action plan. This includes the location of the nearest medical facility and how to contact emergency services. In an emergency, call 911 (or the local equivalent) first, then contact the Divers Alert Network (DAN) at 919-684-9111 for expert medical advice and evacuation coordination.

Hyperbaric oxygen therapy, which involves breathing pure oxygen in a pressurized chamber, is the definitive treatment for serious injuries like DCS and AGE. The sooner it begins, the better the chance of a full recovery. Learn more about Information on diving emergencies from the CDC and the Evaluation and management of diving medical problems.

The Role of the Dive Team and Post-Dive Care

Diving is a team activity, and everyone from your buddy to the boat captain plays a role in diving health and safety. In commercial diving, a dive supervisor oversees the entire operation, while a standby diver is ready for immediate rescue. For recreational divers, your buddy is your primary safety partner for in-water assistance and emergencies. Clear communication before and during the dive is essential.

A good post-dive debrief helps you learn from each experience. Discuss what went well and what could be improved to reinforce good habits.

Flying after diving requires careful timing to avoid DCS. Wait at least 12 hours after a single no-decompression dive, 18 hours after multiple dives, and 24 hours after any decompression diving.

Logging your dives tracks your experience, aids in future dive planning, and provides crucial information for medical personnel in an emergency.

Equipment care is also vital. Rinse your gear with fresh water after every dive, inspect it for damage, and store it properly to ensure it's ready for your next trip.

By following these principles, you can enjoy a long and safe diving life. Dr. Michael B. Strauss has dedicated his career to studying these critical aspects of diving safety. To dive deeper into the subject, get your copy of "Diving Science Revisited" and remember: the best dive is always a safe dive.

DISCLAIMER: Articles are for "EDUCATIONAL PURPOSES ONLY", not to be considered advice or recommendations.