Understanding How You Breathe Underwater

Scuba diving breathing apparatus is the equipment that delivers breathable gas, allowing divers to explore the underwater world. Understanding how these systems work is essential for safety and performance.

The three main types of underwater breathing apparatus are:

Open-Circuit SCUBA: The most common system for recreational diving. The diver inhales from a tank and exhales bubbles into the water.

Rebreathers: Advanced systems that recycle exhaled breath by removing carbon dioxide and adding oxygen, ideal for technical diving and extended underwater time.

Surface-Supplied Systems: Air is delivered through a hose from the surface, used primarily for commercial and scientific diving.

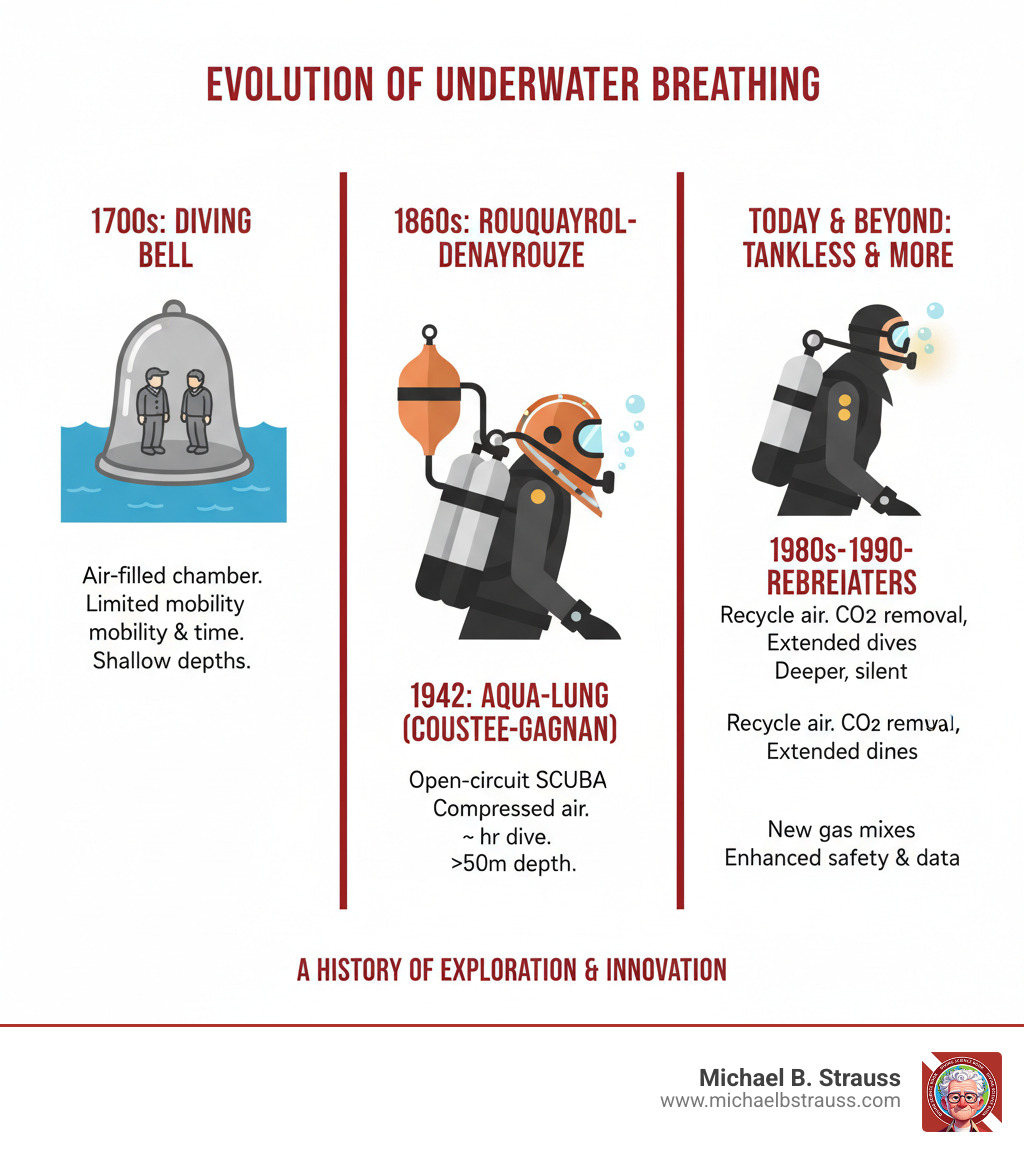

The modern era of diving began in 1942-1943 when engineer Émile Gagnan and Naval Lieutenant Jacques Cousteau invented the Aqua-Lung. This first successful open-circuit SCUBA system revolutionized underwater exploration by allowing dives of over an hour at significant depths.

Today's breathing apparatus has evolved with improved safety features and specialized configurations. Understanding these systems is key to appreciating the engineering that keeps divers safe and the physiological principles that govern every breath underwater.

Basic scuba diving breathing apparatus vocab:

A Deep Dive into Scuba Diving Breathing Apparatus

The world of scuba diving breathing apparatus is surprisingly diverse, ranging from simple recreational gear to sophisticated systems for military and scientific use. Each type of system has unique characteristics suited for different underwater applications. Let's explore what makes each one unique.

| Feature | Open-Circuit SCUBA | Closed-Circuit Rebreathers (CCR) | Surface-Supplied Systems |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gas Efficiency | Low (exhaled gas vented) | High (exhaled gas recycled) | Unlimited (continuous supply from surface) |

| Dive Duration | Limited by tank size and gas consumption | Significantly longer (hours, limited by scrubber/O2) | Very long (limited by surface supply, diver endurance) |

| Complexity | Low to moderate | High (multiple failure points, extensive monitoring) | Moderate (umbilical management, surface crew) |

| Cost | Moderate (initial gear, tank fills) | High (initial gear, consumables, specialized training) | High (equipment, support crew, logistics) |

| Typical Use Cases | Recreational diving, basic instruction, photography | Technical diving, military, scientific, advanced photography | Commercial diving, scientific research, construction |

| Bubbles | Yes, constant stream | Minimal to none | Minimal (exhaust vented via mask/helmet) |

| Stealth | Low | High | Low |

| Warmth | Breath can be cold | Warmer breathing gas (recycled) | Variable (depends on system, water temperature) |

Open-Circuit: The Traditional Scuba Diving Breathing Apparatus

Open-circuit is the classic scuba diving breathing apparatus seen in recreational diving. The principle is simple: you breathe in compressed air from a tank and exhale bubbles into the water. As the name SCUBA (Self-Contained Underwater Breathing Apparatus) implies, everything you need is carried with you.

The core components include:

- High-Pressure Cylinder: The dive tank, typically made of aluminum or steel, holds compressed air at 200-300 bar (2,900-4,400 psi).

- Diving Regulator: This device reduces the tank's high pressure to a breathable level. The first stage attaches to the tank and lowers the pressure to an intermediate level. The second stage (the mouthpiece) is a demand valve that delivers air at the surrounding ambient pressure whenever you inhale.

- Alternate Air Source: A secondary second stage, or "octopus," serves as a backup and allows for sharing air with a buddy in an emergency.

Divers typically wear their tanks in a back-mount configuration, but sidemount diving (with cylinders clipped to the sides) is popular for technical and cave diving. This system is supported by a Buoyancy Control Device (BCD) to manage depth and a Submersible Pressure Gauge (SPG) to monitor remaining air.

Due to its reliability, simplicity, and affordability, open-circuit SCUBA remains the standard for most recreational divers worldwide.

Rebreathers: An Advanced Scuba Diving Breathing Apparatus

Rebreathers are advanced scuba diving breathing apparatus that offer a different experience, especially for technical divers, photographers, and researchers. Instead of exhaling bubbles, a rebreather recycles the diver's breath.

The system works by passing exhaled gas through a carbon dioxide scrubber to remove CO2. Oxygen sensors monitor the gas in the breathing loop (held in a flexible counterlung), and the system injects a precise amount of oxygen to maintain a breathable mix.

- Closed-Circuit Rebreathers (CCRs) recycle nearly all exhaled gas, making them almost bubble-free and highly gas-efficient.

- Semi-Closed Rebreathers (SCRs) are simpler, venting a small amount of gas continuously.

The main advantages are significantly extended dive times (often several hours), silent operation that doesn't disturb marine life, and warmer, moister breathing gas. However, rebreathers are complex, expensive, and have more potential failure points. They demand meticulous maintenance and, most importantly, require extensive, specialized training beyond standard recreational certification from qualified instructors.

Surface-Supplied and Emergency Breathing Systems

Not all divers carry their gas supply. Surface-supplied diving equipment delivers breathing gas from the surface through an umbilical hose. This setup, common in commercial and scientific diving, allows for nearly unlimited dive times and constant communication with a surface crew. A simpler version, hookah diving, is sometimes used for shallow recreational diving.

Even with reliable primary gear, every diver should have a backup. Emergency breathing systems are crucial for handling unexpected out-of-air situations.

- Pony bottles are small, independent cylinders with their own regulators, providing enough air for a controlled ascent.

- Compact emergency breathing units are highly portable mini-SCUBA systems designed for immediate, short-duration use.

- Bailout cylinders are larger independent gas supplies essential for technical divers in overhead environments like caves or wrecks.

These redundant systems are lifesavers in scenarios like equipment malfunction, miscalculated air consumption, or buddy separation.

The Future of Underwater Breathing: Innovations on the Horizon

Innovation in scuba diving breathing apparatus continues, with concepts aiming to reduce bulk and create a more natural diving experience.

Emerging ideas include:

- Human-powered surface air supplies that use a diver's movements to draw air from a surface buoy.

- Integrated helmet systems that combine a rebreather and heads-up display into a single unit.

- Artificial gills that conceptually aim to extract oxygen directly from the water.

While fascinating, these tankless innovations face major problems. Extracting sufficient oxygen from water requires immense energy, and safely managing exhaled carbon dioxide without a traditional scrubber is a significant challenge. Above all, any new technology must meet rigorous safety standards before it can be considered a viable alternative to proven systems. For now, it's wise to approach these concepts with healthy skepticism while appreciating the drive for innovation.

Prioritizing Safety and Looking Ahead

As we've explored the fascinating world of scuba diving breathing apparatus, one truth emerges above all others: our safety depends entirely on our equipment working flawlessly and our knowledge being rock-solid. Every breath we take underwater is a gift of engineering and preparation, whether we're using a simple open-circuit system or a sophisticated rebreather.

Key Safety Considerations for All Breathing Gear

Regardless of the scuba diving breathing apparatus you use, safety is paramount. These principles are non-negotiable:

- Professional Training: Proper education from certified instructors is the foundation of safe diving. This is especially true for complex gear like rebreathers, which require extensive, system-specific training from certified instructors.

- Regular Maintenance: Follow manufacturer service schedules religiously. A well-maintained system is a reliable one.

- Pre-Dive Checks: Methodically inspect your entire breathing system before every dive to catch problems on the surface.

Understanding physiological risks is also critical. Never hold your breath during ascent to avoid lung over-expansion injury. To prevent decompression sickness (DCS), you must understand how pressure changes affect dissolved gases in your body. Learn more about Decompression Science and where DCS can occur. Also, be mindful of carbon dioxide buildup from improper breathing, as well as oxygen toxicity and nitrogen narcosis at depth.

Finally, new devices must undergo rigorous testing to meet safety standards, like those outlined in the US Navy Diving Manual. Proven reliability should always be prioritized.

The Future of Diving and Concluding Thoughts

The evolution of scuba diving breathing apparatus, from the Aqua-Lung to modern rebreathers, is a story of human ingenuity. Future innovations like tankless devices may one day make diving more accessible, but we must maintain perspective. The ocean is an unforgiving environment where our breathing gear is our lifeline. While we can be excited about innovation, it should never come at the expense of proven safety protocols and reliable technology.

Diving offers profound experiences, but it demands preparation, knowledge, and respect. Dr. Michael B. Strauss brings decades of diving medicine expertise to help divers of all levels operate more safely. His comprehensive approach combines medical knowledge with practical experience, reinforcing that knowledge is our most important piece of dive gear—it weighs nothing and can save a life.

A commitment to continuous learning and safety-first practices ensures we can keep exploring the ocean's mysteries for years to come. Ready to deepen your understanding? Explore more at Diving Science with Dr. Michael B. Strauss and get your copy of Diving Science Revisited from Best Publishing Company.

DISCLAIMER: Articles are for "EDUCATIONAL PURPOSES ONLY", not to be considered advice or recommendations.