Why Emergency Preparedness is Critical for Every Diver

Scuba diving emergency procedures are the skills every diver needs to manage underwater emergencies. While scuba diving is a relatively safe sport, the inherent risks mean that when things go wrong, they can escalate quickly.

Essential Scuba Diving Emergency Procedures:

- Prevention: Proper training, dive planning, and equipment checks

- Recognition: Identifying signs of distress in yourself and others

- Response: Immediate actions like air sharing, controlled ascents, and surface signaling

- Rescue: Assisting distressed divers and providing first aid

- Recovery: Post-incident care, documentation, and reporting

Human error, particularly among less trained divers, is a major factor in diving accidents. Dive safety organizations receive thousands of emergency calls annually, many of which could have had better outcomes with proper emergency preparedness.

The golden rule in any diving emergency is simple: Stop. Think. Act.

This structured approach prevents panic and ensures you make the right decisions under pressure. Mastering these procedures is vital for all divers and can mean the difference between a close call and a tragedy.

Proactive Preparedness: Preventing Emergencies Before They Happen

The best emergency is one that never happens. Proactive preparedness is the backbone of safe diving, creating a safety net through training, planning, and preparation to minimize the chance of a dangerous situation underwater.

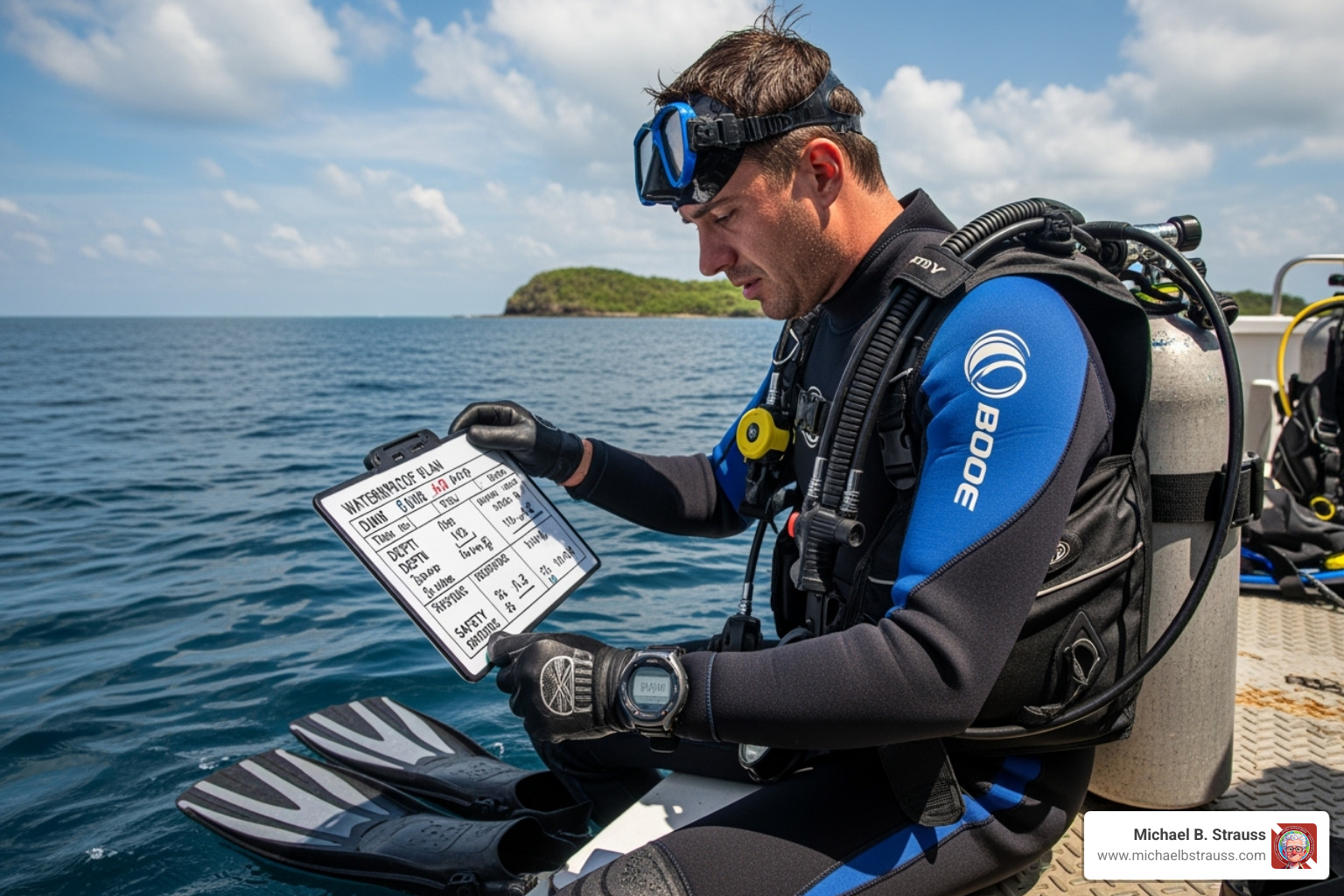

The Foundation: Training, Planning, and Your Emergency Action Plan (EAP)

Your diving education is an ongoing journey. Beyond your Open Water certification, the Rescue Diver course is a valuable investment, teaching you to spot problems early and help others. Since skills fade over time, annual refreshment sessions are crucial to maintain muscle memory and confidence for real emergencies.

The buddy system is a critical safety partnership. Before each dive, review hand signals and emergency plans with your buddy. A good buddy can prevent a minor issue from becoming a major emergency.

Every dive requires a plan. Check weather, know the site, and set depth and time limits. Crucially, you must stick to your plan underwater. Your safety depends on discipline, not chasing distractions.

Create a simple Emergency Action Plan (EAP). This roadmap should include local emergency contacts, the nearest hospital, and the closest decompression chamber. With thousands of emergency calls made to dive safety hotlines annually, a solid EAP is vital.

Essential Gear and Pre-Dive Checks

Your emergency equipment must be in good condition. A first-aid kit with expired supplies or an empty oxygen tank is useless. Inoperable emergency equipment has led to substantial litigation, as courts expect safety gear to be functional. This applies to both operators and individual divers.

Pre-dive checklists save lives. Research confirms that checklists reduce mishaps in high-risk activities, and diving is no exception. A few minutes on a gear check can prevent a major incident.

Equipment maintenance is non-negotiable. Clean, inspect, and store your gear properly after every dive. A well-maintained regulator is reliable when you need it most. Consider it an investment in your safety.

Share important medical information with your buddy and dive staff. If you prefer privacy, write it down, seal it in an envelope, and tell your buddy where to find it. This information can be lifesaving for first responders.

Understanding and Preventing Common Dive Accidents

Knowledge is your best defense. The primary causes of accidents—poor fitness, anxiety, inexperience, poor maintenance, and inadequate planning—are all controllable.

Panic is diving's silent killer. It often starts with minor stressors that accumulate until you feel overwhelmed. The key is to recognize early warning signs in yourself and your buddy before panic takes over.

Cardiovascular problems are the leading cause of drowning among divers. This highlights the importance of good physical fitness and avoiding diving when unwell or fatigued.

Out-of-air scenarios can result from poor gas management, equipment failure, or distraction. Training in gas management and alternate air source use is essential.

Decompression Sickness (DCS), or "the bends," is caused by ascending too quickly, allowing nitrogen bubbles to form in the body. Symptoms like joint pain, fatigue, or dizziness can appear up to 24 hours later and require immediate medical attention. For more on this topic, Diving Science offers in-depth information.

Lung over-expansion injuries like Arterial Gas Embolism (AGE) and pneumothorax are among the most serious diving emergencies, caused by holding your breath or ascending too fast. AGE involves air bubbles entering the bloodstream and traveling to the brain, while pneumothorax is a collapsed lung.

Prevention is critical. Ascend no faster than 18 meters (60 feet) per minute, slowing as you near the surface. Always perform a safety stop at 5 meters (15 feet) for at least three minutes to allow nitrogen to off-gas safely.

Your physical condition is key to safety. Stay hydrated, fit, and never dive when dehydrated, hungover, or exhausted. These factors increase your risk of needing scuba diving emergency procedures. The ocean will wait; don't risk your safety.

Reactive Response: Mastering In-Water Scuba Diving Emergency Procedures

Even with the best preparation, emergencies happen. When they do, your ability to react calmly and effectively with practiced scuba diving emergency procedures is what matters most. This is where your training comes into play.

Immediate Actions: Your Step-by-Step Guide to Scuba Diving Emergency Procedures

In an underwater emergency, resist the urge to rush. Follow the golden rule: Stop. Think. Act. This prevents you from becoming another victim. First, assess for hazards and ensure your own safety. A moment to breathe deeply projects calm confidence, which is as contagious as panic.

After securing your safety, focus on the distressed diver. The priority is getting air to them. If their regulator is in, hold it there. If not, don't waste time trying to reinsert it; focus on a safe ascent to the surface.

Master regulator recovery and clearing. If your regulator is dislodged, recover it by sweeping your arm or reaching for the hose. Clear it by exhaling forcefully or using the purge button. Practice this until it's an automatic response.

If your primary regulator fails, immediately bailout to your alternate gas source. Air-sharing drills build the muscle memory needed for a real emergency.

Out-of-air or equipment malfunction situations may require an emergency ascent. This must be a controlled, not panicked, process. Keep your regulator in, look up, stay relaxed, and breathe continuously to prevent lung over-expansion. If possible, perform a safety stop.

At the surface, establishing buoyancy is the next critical step. Fully inflate the distressed diver's BCD and ditch weights if necessary. Keeping their head above water is vital.

Once buoyant, signal for help immediately. Use any available device: a highly visible Surface Marker Buoy (SMB), a whistle, or a signal mirror. If diving from a boat, radio contact is the fastest way to get support.

Rescue and First Aid: Advanced Scuba Diving Emergency Procedures

With the immediate crisis managed and help en route, your role shifts to rescue and first aid. These advanced scuba diving emergency procedures require specific training, like that from a Rescue Diver course.

For a trapped diver, stay calm and work methodically. Use a dive knife or shears to carefully cut them free from mess. Rushing can make the situation worse.

Towing techniques are essential for moving a distressed diver to safety. Choose the appropriate method based on the diver's consciousness and your energy level, such as a side-by-side tow for a conscious diver or a tank tow for an unconscious one.

Getting a victim out of the water is challenging, especially if they are unconscious. It requires coordination among multiple helpers to protect the victim's airway while managing the weight of their gear.

Once out of the water, perform an ABC assessment: Airway, Breathing, Circulation. Check for a clear airway, normal breathing, and a pulse. This systematic approach is critical.

If there is no breathing and no pulse, begin CPR administration immediately. Give 30 chest compressions (100-120 per minute) followed by two rescue breaths. Continue this 30:2 cycle. Use a barrier device for protection.

Oxygen administration is the most important first aid for most diving accidents. Provide 100% oxygen to any diver with a suspected injury, even if they seem fine. Proper training and adequate supplies can dramatically improve outcomes.

Treat for shock by maintaining body temperature with blankets, positioning them appropriately, continuing oxygen, and withholding oral fluids from an unconscious person.

Dr. Michael B. Strauss's work, such as Evaluation and Management of Pain-Related Medical Problems of Diving, offers crucial medical perspectives on diving emergencies.

Post-Incident Protocol and Continuous Improvement

Post-incident actions are as crucial as the immediate response for the victim's care and for preventing future accidents.

Document the incident thoroughly while details are fresh. Record max depth, dive time, and a symptom timeline. This information is vital for medical professionals. Photos can also serve as important documentation.

Report the incident to authorities and relevant dive safety organizations to help the community learn. Contact a dive safety hotline after activating EMS or for management guidance. Accurate incident reports contribute to safety research and help prevent future accidents.

In serious accidents, preserve the victim's dive gear as-is. Do not adjust or disassemble it. The equipment may be needed for investigation to determine what went wrong.

Understand the role of insurance and litigation. Proper insurance is essential for dive operations. Inadequately equipped operators have faced significant legal consequences, reinforcing the need for functional equipment and trained staff.

Thoroughly vet third-party operators. Check their qualifications, emergency procedures, equipment, and insurance coverage. Uninsured partners pose a significant liability risk.

Regularly evaluate your Emergency Action Plan. Review it every few months, check supplies, practice scenarios, and incorporate lessons learned. This continuous improvement cycle ensures your response remains effective.

This comprehensive approach to preparedness creates a culture of safety. We encourage every diver to Continue your dive safety education and explore the knowledge in Dr. Michael B. Strauss's comprehensive diving books. A commitment to preparation and learning helps keep diving safe and thrilling.

Get your copy of Diving Science Revisited here: https://www.bestpub.com/view-all-products/product/diving-science-revisited/category_pathway-48.html

DISCLAIMER: Articles are for "EDUCATIONAL PURPOSES ONLY", not to be considered advice or recommendations.