Why Understanding Scuba Diving Medical Conditions Matters for Safe Underwater Trips

While scuba diving is a remarkably safe activity when proper procedures are followed, certain medical conditions can significantly increase the risk of injury or even death underwater. Understanding these risks is the first step toward safe diving.

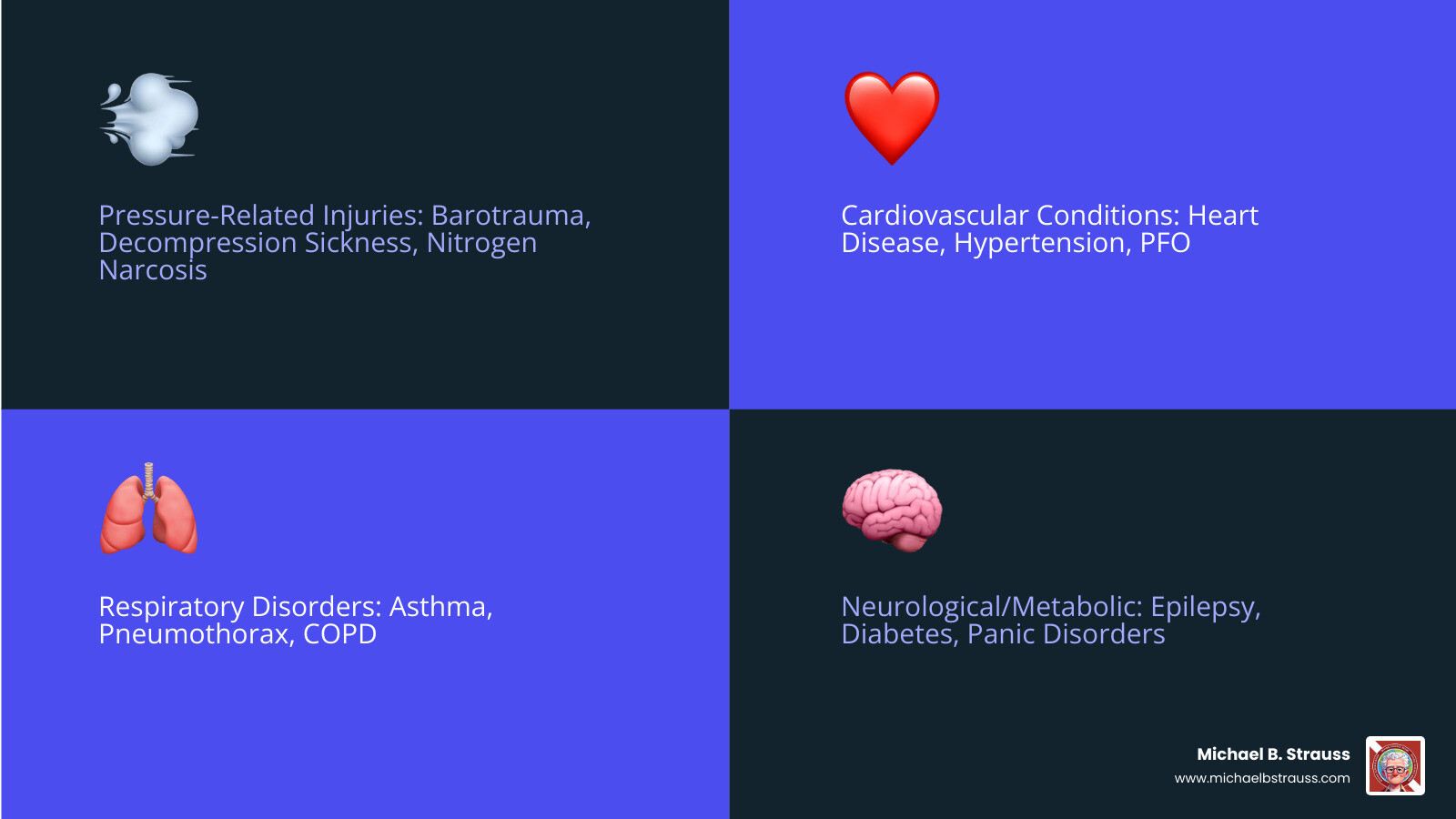

Key Medical Conditions That Can Affect Diving Safety:

- Pressure-Related Injuries: Barotrauma (ear, sinus, lung damage), Decompression Sickness ("the bends"), Arterial Gas Embolism

- Cardiovascular Conditions: Heart disease, hypertension, Patent Foramen Ovale (PFO)

- Respiratory Disorders: Asthma, COPD, history of spontaneous pneumothorax

- Neurological Conditions: Epilepsy, seizure disorders, migraines with aura

- Metabolic Disorders: Diabetes

- Psychological Conditions: Panic disorder, severe anxiety, claustrophobia

The underwater environment places unique stresses on the body. As a diver descends, increasing water pressure affects gas volumes and absorption in the body. For example, more nitrogen dissolves into the bloodstream at depth. If a diver ascends too quickly, this nitrogen can form bubbles, leading to decompression sickness.

Statistics show that nearly 30% of recreational diving fatalities involve a cardiac event as the primary cause, highlighting the critical importance of medical screening before diving.

Fortunately, many conditions that were once considered absolute contraindications—like well-controlled asthma or diabetes—may now be manageable. The key is to consult with a diving medicine specialist to assess your individual fitness to dive.

Quick scuba diving medical conditions terms:

Understanding Key Scuba Diving Medical Conditions and Contraindications

The underwater world presents unique challenges to the human body. The increased pressure affects us in ways we don't experience on land, making it crucial to understand how certain medical conditions can become significant safety risks.

Pressure-Related Injuries: Barotrauma and Decompression Illness (DCI)

Pressure-related injuries are the most common ailments in diving. They occur when the pressure in your body's air spaces doesn't equalize with the surrounding water pressure.

- Barotrauma: This is an injury from pressure imbalance. Ear barotrauma is the most frequent, causing pain or even a ruptured eardrum if you can't equalize properly during descent. Sinus barotrauma is similar, caused by congestion that traps air in the sinuses. The most dangerous is lung barotrauma, which can happen if you hold your breath during ascent, leading to a collapsed lung or forcing air bubbles into the bloodstream.

- Decompression Illness (DCI): This term covers two conditions caused by nitrogen bubbles forming in the body during or after ascent.

- Decompression Sickness (DCS): Often called "the bends," this happens when dissolved nitrogen comes out of solution too quickly, forming bubbles in tissues and blood. This can cause anything from joint pain to paralysis. Following dive tables or a computer is essential to manage your ascent rate and prevent DCS.

- Arterial Gas Embolism (AGE): This is the most severe form of DCI. It occurs when a lung over-pressurization injury forces air bubbles directly into the arterial bloodstream, where they can travel to the brain and cause stroke-like symptoms. AGE is a life-threatening emergency requiring immediate medical attention.

Further reading: Decompression Science, Why and at What Sites Decompression Sickness Can Occur.

Cardiovascular and Respiratory Health Risks

Your heart and lungs work harder underwater. Pre-existing conditions in these systems can pose serious risks.

Cardiovascular Conditions:

- Hypertension (High Blood Pressure): If well-controlled with medication, diving may be possible. Uncontrolled hypertension is a significant risk factor.

- Coronary Artery Disease: A history of heart attack or bypass surgery requires a thorough evaluation, including a stress test, to ensure you can handle the physical demands of diving.

- Patent Foramen Ovale (PFO): This is a small hole between the heart's upper chambers, present in about 25% of the population. It can allow nitrogen bubbles to bypass the lungs' filtering effect, increasing the risk of neurological DCS.

- Immersion Pulmonary Edema (IPO): A serious condition where fluid builds up in the lungs during immersion, causing shortness of breath. It's a leading cause of non-error-related diving fatalities.

Further reading: Mammalian Diving Reflex.

Respiratory Conditions:

- Asthma: Once a complete ban, diving with asthma is now sometimes possible if it's mild, well-controlled, and you pass a fitness-to-dive medical exam. The main concern is air-trapping, which can lead to lung over-expansion on ascent.

- Spontaneous Pneumothorax (Collapsed Lung): This is a near-absolute contraindication to diving due to the high risk of recurrence and severe lung injury under pressure.

Neurological, Metabolic, and Other Systemic Concerns

- Epilepsy and Seizure Disorders: These are generally considered absolute contraindications. A seizure underwater would almost certainly be fatal.

- Diabetes Mellitus: With modern management, many people with diabetes can dive safely. This requires excellent blood sugar control, no significant diabetes-related complications, and careful monitoring before and after every dive.

- Obesity: While not a direct disqualifier, obesity increases the risk of decompression sickness and can reduce overall fitness, making it harder to handle gear and potential emergencies.

- Pregnancy: This is an absolute contraindication. The effects of pressure and dissolved nitrogen on a developing fetus are unknown and potentially harmful.

- Anxiety and Panic Disorders: The underwater environment can be a trigger for anxiety or panic, which is extremely dangerous. A calm and rational mindset is critical for safe diving.

Further reading: Resources.

Understanding these scuba diving medical conditions is about empowering yourself to make safe decisions. Always consult a physician, preferably one with expertise in diving medicine, to assess your fitness to dive.

Prevention, Management, and Special Diving Populations

Safe diving is about being proactive. By understanding how to prevent injuries and considering the specific needs of different divers, you can ensure your underwater trips are both thrilling and safe.

How to Prevent and Treat Diving Injuries

Prevention is always better than cure, especially in diving. Most injuries are avoidable by following established safety protocols.

Key Prevention Strategies:

- Get Medically Cleared: Before you start diving, get a medical evaluation from a doctor, ideally one familiar with diving medicine. This helps identify any underlying scuba diving medical conditions that could pose a risk.

- Master Essential Skills: Practice equalization techniques consistently to prevent ear and sinus barotrauma. Never force it; if you can't equalize, ascend slightly and try again.

- Control Your Ascent: Ascend slowly, no faster than 9 meters (30 feet) per minute. A slow ascent allows your body to safely off-gas dissolved nitrogen.

- Always Do a Safety Stop: A 3-5 minute stop at 5 meters (15 feet) is a crucial best practice that significantly reduces your risk of decompression sickness (DCS).

- Use Your Dive Computer: Plan your dives conservatively and always stay within the no-decompression limits indicated by your computer or dive tables.

- Stay Hydrated and Rested: Dehydration is a major risk factor for DCS. Drink plenty of water and ensure you're well-rested before diving.

- Never Hold Your Breath: This is the golden rule of scuba. Breathing continuously, especially on ascent, prevents lung over-expansion injuries.

- Dive with a Buddy: Your buddy is your primary safety resource underwater. Always dive with a partner you trust.

- Listen to Your Body: If you don't feel 100%, don't dive. It's never worth the risk.

In Case of an Emergency:

If you suspect a diver has Decompression Illness (DCI), including DCS or an Arterial Gas Embolism (AGE), act fast:

- Administer 100% Oxygen: This is the most important first aid step.

- Keep the Diver Lying Down: This helps stabilize their condition.

- Seek Immediate Medical Help: Contact local emergency services and the Divers Alert Network (DAN) for expert guidance.

The definitive treatment for DCI is Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy (HBO), where the patient breathes pure oxygen in a pressurized chamber. For minor barotrauma, rest and avoiding diving until healed is usually sufficient, though a doctor's visit is recommended.

For more in-depth information, you can read about the Evaluation and Management of Pain-Related Medical Problems of Diving or find a trusted diving doctor through the UK DMC Medical Referees.

Considerations for Different Divers

Children: The key factor isn't just age, but physical and emotional maturity. A child must be able to understand the risks, follow instructions, and handle the equipment safely.

Women: While diving is equally safe for women, some studies suggest a potential link between the menstrual cycle and DCS risk. Pregnancy is an absolute contraindication to diving. Breast implants are generally not a concern.

Older Adults: As we age, fitness levels can decline and the likelihood of pre-existing conditions (like heart disease or hypertension) increases. A thorough medical evaluation by a diving specialist is crucial to ensure any health issues or medications won't pose a risk underwater.

What is the Recommended Waiting Period Before Flying After Diving?

Flying too soon after diving can cause decompression sickness (DCS) because the pressure in an aircraft cabin is lower than at sea level. This pressure drop can cause dissolved nitrogen in your body to form dangerous bubbles. The Divers Alert Network (DAN) provides these minimum guidelines:

- After a single no-decompression dive: Wait at least 12 hours.

- After multiple dives per day or several days of diving: Wait at least 18 hours.

- After dives requiring decompression stops: Wait more than 18 hours (24 hours is often recommended).

Always err on the side of caution. It's better to wait a little longer than to risk a serious medical emergency.

For detailed research, you can explore DAN's research on flying after diving.

For a comprehensive guide to the science of diving, purchase your copy of "Diving Science Revisited" from Best Publishing Company.

DISCLAIMER: Articles are for "EDUCATIONAL PURPOSES ONLY", not to be considered advice or recommendations.