What Are the Real Risks of Scuba Diving?

Scuba diving risks are real but manageable dangers that every diver should understand before entering the underwater world. While scuba diving has an average risk of death of 1 in 200,000 dives, most incidents stem from preventable human errors rather than unavoidable hazards.

The main categories of scuba diving risks include:

- Physiological risks - Decompression sickness, nitrogen narcosis, oxygen toxicity

- Equipment-related risks - Regulator failure, buoyancy control issues, breathing gas depletion

- Environmental risks - Strong currents, poor visibility, marine life encounters

- Human factors - Poor judgment, inadequate training, buddy system failures

The research shows that human error accounts for 85-90% of diving accidents. This means most risks can be prevented through proper training, careful planning, and following established safety protocols.

As Jacques Cousteau famously described nitrogen narcosis as the "rapture of the deep," diving presents unique challenges that don't exist on land. Your body wasn't designed for the underwater environment, where pressure changes affect every air-filled space and dissolved gases behave differently.

The good news? With proper education and preparation, recreational diving maintains fatality rates comparable to jogging or driving. Understanding these risks isn't meant to scare you away from diving - it's meant to help you dive safely for years to come.

The key is recognizing that while diving involves inherent dangers, they're well-understood and largely preventable through training, equipment maintenance, and smart decision-making underwater.

The Unseen Dangers: A Deep Dive into Physiological Scuba Diving Risks

While you float weightlessly underwater, your body is dealing with serious physics. Understanding these internal processes is crucial for recognizing scuba diving risks before they become dangerous.

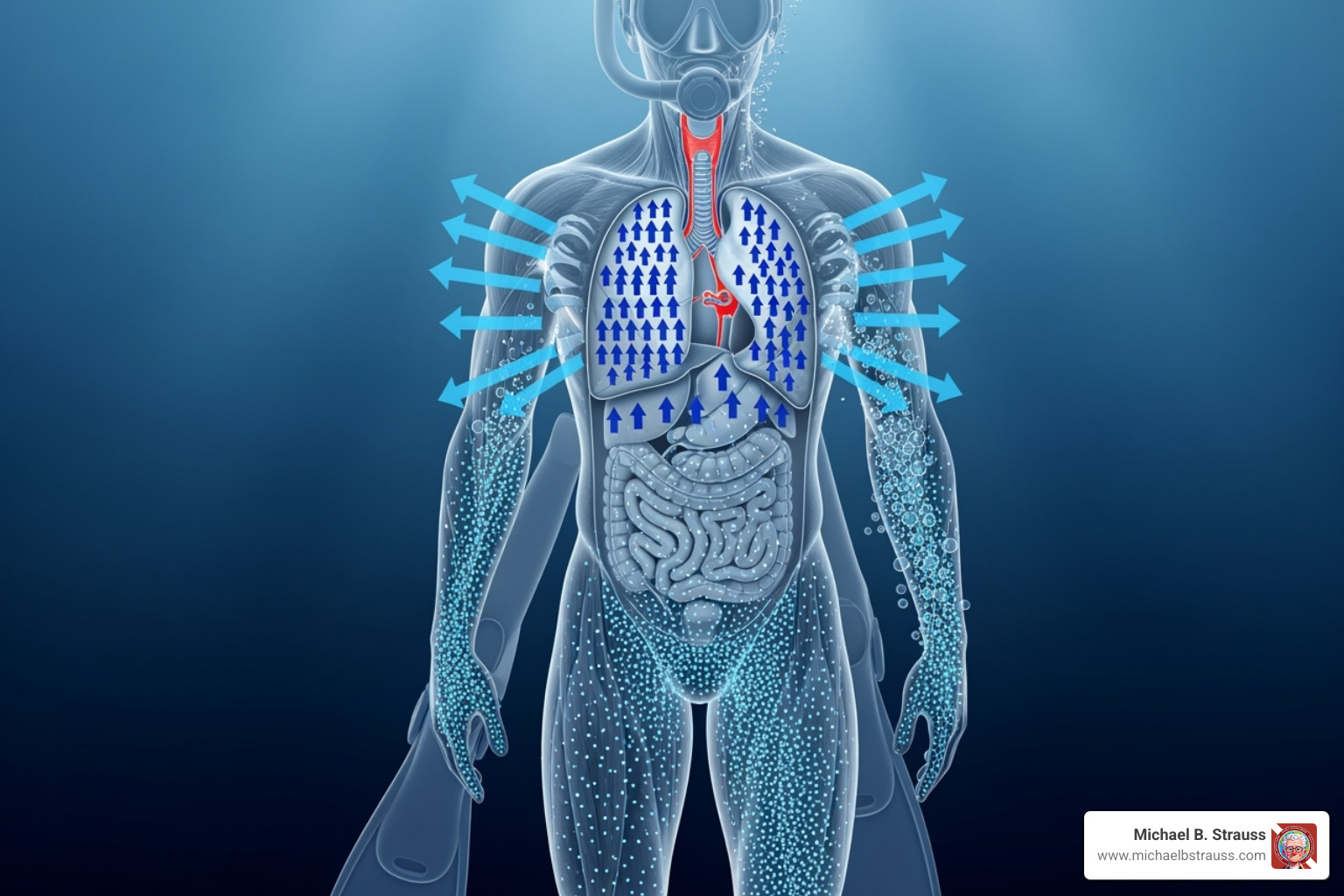

Two laws are fundamental. Boyle's Law explains that as pressure increases on descent, the gas in your body's air spaces compresses; on ascent, it expands. Henry's Law dictates that the deeper you go, the more nitrogen dissolves into your blood and tissues. This dissolved nitrogen is the source of many of diving's most serious physiological risks. Your ears, sinuses, and lungs constantly adjust to these pressure changes, and problems arise when that adjustment fails.

Decompression Illness (DCI): Understanding "The Bends" and Beyond

This is where the gas laws matter. Decompression Illness (DCI) covers two problems that can turn a dive into a medical emergency: Decompression Sickness and Pulmonary Overinflation Syndrome.

Decompression Sickness (DCS), or "the bends," happens when you ascend too quickly. Dissolved nitrogen forms bubbles in your bloodstream, blocking blood flow and damaging tissue. DCS occurs in 1 to 35 cases per 10,000 dives.

- Type I DCS is milder, causing joint pain, skin mottling, or itching. Any DCS requires medical attention.

- Type II DCS is serious, affecting the brain or spinal cord. It causes neurological symptoms like numbness, paralysis, blurred vision, or confusion and requires immediate treatment.

Pulmonary Overinflation Syndrome (POIS) occurs if you hold your breath during ascent. Expanding air can rupture your lungs.

- The most dangerous form is Arterial Gas Embolism (AGE), where air bubbles enter the bloodstream and travel to the brain or heart. Symptoms appear within 10 minutes of surfacing and resemble a stroke: dizziness, paralysis, or loss of consciousness.

- Pneumothorax is a collapsed lung caused by air leaking into the chest cavity.

Symptoms of DCI can appear up to 48 hours post-dive. For deeper insights, see this scientific research on Decompression Illness and explore more information about Decompression Science.

Risk factors include: deeper or longer dives, rapid ascents, dehydration, poor fitness or obesity, increasing age, alcohol or tobacco use, pre-existing conditions, cold water, and fatigue.

Gas-Related Hazards: Nitrogen Narcosis and Oxygen Toxicity

Even with perfect decompression, other gases pose risks.

Nitrogen narcosis, the "rapture of the deep," feels like being drunk underwater. It typically begins around 66 feet and affects nearly everyone by 132 feet. Symptoms include euphoria, disorientation, and impaired judgment. The danger lies in the poor decisions you might make while narced. The effect is reversible; ascending to shallower water clears your head.

Oxygen toxicity is a concern when diving with enriched air (nitrox) or rebreathers. Too much oxygen under pressure is poisonous.

- Central Nervous System (CNS) toxicity is the most acute form, causing convulsions, tunnel vision, or nausea. A convulsion underwater is life-threatening, which is why divers adhere to partial pressure limits of 1.4 bar.

- Pulmonary oxygen toxicity affects the lungs after prolonged exposure, causing chest pain and coughing.

Careful planning and staying within established limits prevent both problems.

Environmental and Equipment-Related Scuba Diving Risks

Beyond physiological issues, your gear and the environment present other scuba diving risks.

Drowning is often the final result of another problem, not the initial cause. A diver might drown after panicking, losing consciousness, or running out of air due to another issue.

Equipment failure, though rare with modern gear, can escalate problems.

- Regulator malfunctions include free-flows or restricted airflow.

- Buoyancy compensator issues can cause uncontrolled ascents or descents.

- Gas depletion from poor planning can trigger panic and dangerous emergency ascents.

The diving environment presents its own challenges. Strong currents can separate divers from their buddy or boat. Poor visibility can cause disorientation, especially in overhead environments. While encounters with hazardous marine life are rare, venomous or aggressive animals require distance.

Problem in fishing lines or nets contributes to about 20% of fatal diving accidents, highlighting the need for specialized training for overhead environments. Most of these risks are manageable with proper training, planning, and equipment maintenance.

Staying Safe Beneath the Waves: Prevention, Training, and Best Practices

Here's the wonderful truth about scuba diving risks - they're almost entirely preventable. Your safety underwater isn't left to chance; it's built on a foundation of solid preparation, continuous learning, and smart decision-making. Think of diving safety like learning to drive a car. The roads can be dangerous, but with proper training and defensive driving habits, millions of people steer them safely every day.

The key is taking personal responsibility for your safety while embracing the buddy system that makes diving both safer and more enjoyable.

The Foundation of Safety: Training, Planning, and the Buddy System

Your journey to safe diving starts long before you ever get wet. Quality training from reputable certification agencies forms the bedrock of diving safety. Your Open Water course isn't just about learning to breathe underwater - it's about understanding how your body responds to pressure, how to handle equipment failures, and how to make smart decisions when things don't go as planned.

But here's something many new divers don't realize: your education never really ends. Advanced training and specialty courses aren't just for show - they're your insurance policy against the unexpected. Each course builds on your foundation, teaching you to handle deeper dives, steer wrecks safely, or manage the unique challenges of night diving.

Dive planning might sound boring, but it's actually your best friend underwater. Think of it as your roadmap to a successful dive. Smart gas management means knowing exactly how much air you need, tracking your consumption rate, and always surfacing with at least 50 Bar (500 PSI) remaining in your tank. Running out of air underwater is like running out of gas in the middle of nowhere - except the consequences are far more serious.

No-decompression limits (NDLs) aren't suggestions - they're your safety net against decompression sickness. Whether you're using dive tables or a dive computer, these limits are calculated to keep dissolved nitrogen in your tissues at safe levels. Modern dive computers have revolutionized dive safety by continuously monitoring your depth and time, but they're only as good as the diver who follows their guidance.

Environmental assessment before each dive can save your life. Checking weather conditions, understanding current patterns, and assessing visibility aren't just professional habits - they're common sense. If conditions look sketchy, there's no shame in calling off a dive. The ocean will be there tomorrow.

The buddy system deserves special attention because the statistics are sobering: solo diving has a ten-times higher fatality rate than buddy diving. Your buddy isn't just company - they're your safety backup, your second set of eyes, and your lifeline in an emergency. Those pre-dive buddy checks might feel routine, but they catch equipment problems before they become underwater emergencies.

For comprehensive diving safety resources and ongoing education, the Divers Alert Network provides invaluable research, training, and specialized support for divers worldwide. They're the go-to authority for diving safety and medical information.

Mitigating Physiological Scuba Diving Risks: Ascent, Buoyancy, and Health

Prevention of physiological scuba diving risks comes down to understanding your body's limitations and working within them. The most critical skill you can master is the slow, controlled ascent with safety stops. This isn't just a recommendation - it's your primary defense against both decompression sickness and lung overexpansion injuries.

Ascending no faster than 30 feet per minute gives dissolved nitrogen time to safely leave your tissues. Think of it like opening a soda bottle slowly versus popping it open quickly. The slow approach prevents those dangerous bubbles from forming. Safety stops at 15-20 feet for 3-5 minutes provide an extra margin of safety, giving your body additional time to off-gas nitrogen safely.

Buoyancy control and proper weighting are fundamental skills that directly impact your safety. When you're properly weighted and neutrally buoyant, you're not fighting the water - you're working with it. Poor buoyancy control leads to rapid ascents or descents, both of which can trigger serious medical problems. Getting your weighting right might take a few dives, but it's worth the effort.

Your physical fitness and hydration status play bigger roles in diving safety than many people realize. Regular aerobic exercise improves your body's ability to eliminate inert gases, while maintaining a healthy body fat percentage reduces your susceptibility to decompression sickness. Staying well-hydrated before, during, and after dives improves blood flow and helps your body eliminate nitrogen more efficiently.

Avoiding alcohol and drugs before diving isn't just about impaired judgment - though that's certainly a concern. These substances affect your body's physiological responses, making you more susceptible to decompression sickness and reducing your ability to handle emergencies.

Honest pre-dive health assessments can prevent serious problems before they start. That cold you're fighting might seem minor, but it can lead to serious ear or sinus injuries underwater. Heart conditions, lung problems, or even certain medications can increase your diving risks significantly.

Emergency Preparedness and First Aid for Divers

Even with perfect prevention, emergencies can still happen. Being prepared isn't pessimistic - it's practical. Recognizing symptoms of decompression illness or lung overexpansion injuries can make the difference between a minor incident and a major tragedy. Joint pain, numbness, confusion, or difficulty breathing after a dive should always be taken seriously, even if symptoms appear hours later.

Every dive should have an Emergency Action Plan (EAP). This means knowing local emergency numbers, the location of the nearest recompression chamber, and how to contact emergency services from your dive site. If you're diving from a boat, make sure the operator has current emergency contact information and communication equipment.

Surface oxygen administration is the most important first aid you can provide for suspected decompression illness. One hundred percent oxygen helps reduce bubble size and assists nitrogen elimination, buying precious time while arranging transport to definitive medical care. This is why serious divers always carry emergency oxygen in their dive kit.

Hyperbaric chamber treatment remains the gold standard for treating decompression illness and arterial gas embolism. These specialized medical facilities can literally put a diver "back down" to pressure, then slowly decompress them while breathing pure oxygen. Time is critical - the sooner treatment begins, the better the outcome.

A well-stocked diver's first aid kit should include an emergency oxygen system with demand valve, basic first aid supplies like bandages and antiseptic wipes, seasickness medication, signaling devices like a whistle and mirror, emergency contact information, and a dive knife for mess situations.

Dr. Michael B. Strauss's comprehensive diving books provide deeper insights into diving science and emergency procedures. His expertise in diving medicine offers invaluable guidance for divers seeking to understand the physiological challenges of the underwater environment.

By understanding these scuba diving risks and committing to prevention and preparedness, you're setting yourself up for years of safe, enjoyable diving adventures. The underwater world is incredibly rewarding for those who approach it with knowledge, respect, and proper preparation.

To dive deeper into the science behind safe diving, get your copy of Diving Science Revisited.

DISCLAIMER: Articles are for "EDUCATIONAL PURPOSES ONLY", not to be considered advice or recommendations.