Understanding Decompression Sickness: From Bubbles to Bends

What causes DCS is a critical question for anyone exposed to significant pressure changes, including divers, aviators, and astronauts. Decompression Sickness (DCS), or "the bends," occurs when dissolved gases—primarily nitrogen—form bubbles in tissues and the bloodstream following a rapid decrease in surrounding pressure.

Quick Answer: Primary Causes of DCS

- Rapid ascent from depth - Ascending too quickly while scuba diving without proper decompression stops

- Exposure to high altitude - Flying in unpressurized aircraft or ascending to altitude after diving

- Inadequate off-gassing time - Not allowing dissolved nitrogen to safely exit tissues

- Pressure reduction - Any situation where ambient pressure drops faster than your body can safely eliminate inert gases

Think of it like opening a carbonated drink: the sudden pressure drop causes bubbles to form instantly. This is what happens inside your body during DCS. These bubbles can block blood flow, damage tissues, and cause symptoms from joint pain to paralysis.

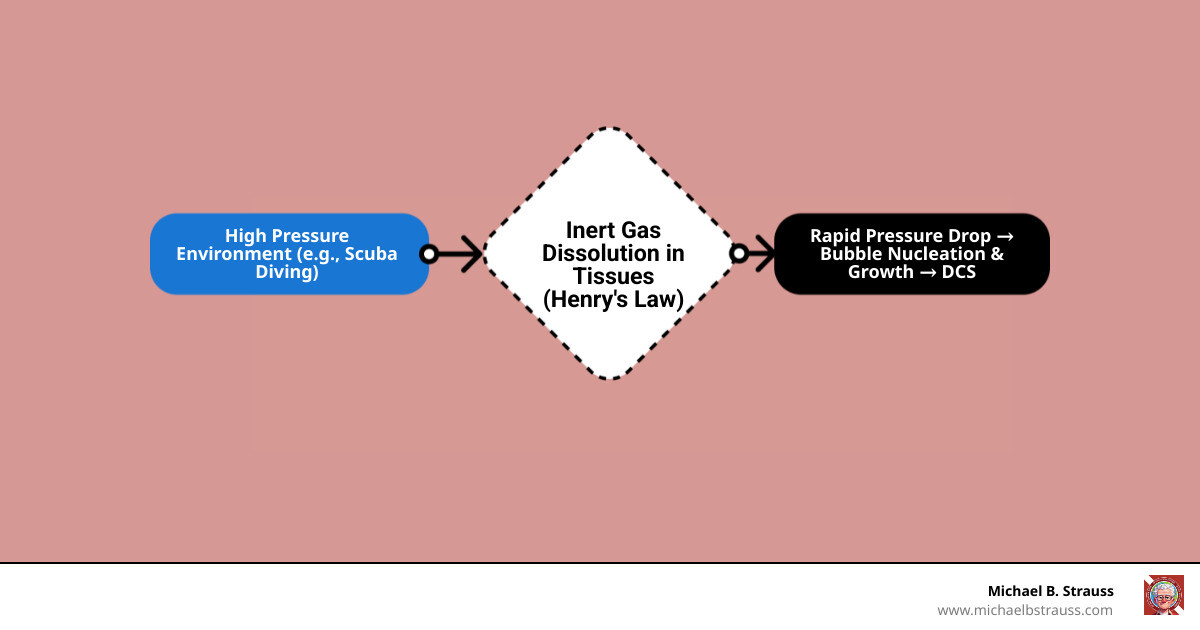

This condition is governed by Henry's Law: the amount of gas dissolved in a liquid is proportional to the pressure. Under high pressure (like underwater), your body absorbs extra nitrogen. If that pressure decreases too quickly, the nitrogen comes out of solution as bubbles because it doesn't have time to be exhaled safely. While diving is the most common cause, affecting approximately 1,000 U.S. scuba divers annually, DCS also occurs in aviators, astronauts, and construction workers in pressurized environments. For a deeper look at the science, explore our resources on Decompression Science.

Handy What causes DCS terms:

What are the Symptoms of DCS?

DCS is known as "the great imitator" because its symptoms can mimic many other conditions, depending on where bubbles form. Here are the most common signs:

- Joint pain ("the bends"): The most frequent symptom (60-70% of cases). This deep, aching pain, often in the shoulders, can be severe enough to cause a person to double over.

- Neurologic symptoms: Occurring in 10-15% of cases, these serious symptoms include headache, dizziness, confusion, visual disturbances, numbness, weakness, paralysis, and extreme fatigue.

- Skin manifestations: Affecting 10-15% of cases, symptoms include itching and a mottled or marbled skin rash (cutis marmorata).

- Pulmonary DCS ("the chokes"): A rare but dangerous form causing chest pain, shortness of breath, and a dry cough.

- Other symptoms: Nausea, ringing in the ears, and difficulty urinating.

Symptom Onset: In 95% of cases, symptoms appear within 24 hours of the pressure exposure. However, onset can be immediate or delayed, especially if flying occurs soon after diving.

What Causes DCS? A Deep Dive into Primary Triggers and Risk Factors

Understanding what causes DCS means looking at the physics, environmental conditions, and individual vulnerabilities that lead to bubble formation. It’s all about managing pressure.

The Physics Behind the Bubbles

The physics of DCS is governed by Henry's Law. Under high pressure, inert gases like nitrogen dissolve into body tissues. If pressure drops too quickly on ascent, this nitrogen doesn't have time to be exhaled. Instead, it forms bubbles in tissues and the bloodstream. Because our bodies don't metabolize nitrogen, this accumulated gas must be released slowly to prevent bubble formation. For a detailed explanation of where these bubbles cause problems, we recommend reading our article on Why and at What Sites Decompression Sickness Can Occur.

Diving-Related Causes of DCS

Diving is the most common activity associated with DCS. Key risk factors include:

- Dive Depth and Duration: Deeper and longer dives increase inert gas absorption, directly raising DCS risk, especially without proper decompression stops.

- Ascent Rate: A rapid ascent is a primary cause. Ascending slowly is crucial to allow dissolved nitrogen to be safely exhaled.

- Decompression Stops: Skipping or shortening planned decompression stops during ascent prevents safe nitrogen release and dramatically increases risk.

- Repetitive Dives: Multiple dives in a short time frame cause nitrogen to accumulate. Longer surface intervals are required to off-gas safely.

- Breathing Gas Mixture: Using enriched air nitrox (less nitrogen) can reduce nitrogen uptake but introduces a risk of oxygen toxicity at shallower depths, requiring careful planning of Equivalent Air Depth (EAD).

- Cold Water Diving: Cold water can affect circulation. While it may reduce gas uptake at depth, warming too quickly on ascent (e.g., hot showers) can promote bubble formation.

- Post-Dive Exercise: Strenuous exercise after a dive can stimulate bubble formation. In contrast, mild exercise during the final ascent phases may aid gas elimination.

What Causes DCS in Aviation and Other Environments?

DCS isn't limited to diving. Significant pressure changes in other environments are also a cause.

- Altitude-Induced DCS: Occurs at high altitudes (typically above 18,000 ft, with most cases above 25,000 ft) due to low barometric pressure causing dissolved nitrogen to form bubbles.

- Flying After Diving: This is a dangerous combination. The reduced cabin pressure of an aircraft (equivalent to about 8,000 ft) can trigger DCS in a diver with residual nitrogen. Wait at least 24 hours after diving before flying.

- Oxygen Pre-breathing: A key preventive measure for aviators and astronauts. Breathing 100% oxygen before exposure to low pressure helps eliminate nitrogen from the body, reducing bubble formation risk. For more, see the Aerospace Decompression Illness research.

- Other Environments: Historically, DCS was a hazard for workers in pressurized caissons used for underwater construction.

Individual Risk Factors and Susceptibility

Personal physiology and choices influence what causes DCS in any given person.

- Body Fat Content: Fat tissue stores more nitrogen, so a higher body fat content increases the body's nitrogen load and DCS risk.

- Age: Older individuals may have reduced circulation and slower gas elimination, increasing susceptibility.

- Dehydration: While its primary role is debated, good hydration is crucial for healthy circulation and gas transport, making it a best practice for prevention.

- Physical Fitness: Good aerobic fitness is associated with more efficient gas exchange and can contribute to a lower DCS risk.

- Previous Injury: An existing injury can create areas of altered circulation that may be more prone to bubble formation.

- Alcohol Use: Alcohol contributes to dehydration and impairs judgment, increasing risk.

- Patent Foramen Ovale (PFO): A common heart condition (in ~20% of adults) where a small opening allows venous bubbles to bypass the lungs and enter arterial circulation. This significantly increases the risk of serious neurological DCS. Learn more from Scientific research on PFO and DCS risk.

Prevention and Treatment: Your Guide to Safe Diving and Flying

Knowing what causes DCS is the first step; the next is understanding how to prevent it and, if it occurs, how to treat it. The goal is to keep every adventure safe.

Diagnosis and Immediate First Aid

If DCS is suspected, prompt action is critical. Diagnosis relies on a history of pressure exposure and a thorough symptom and neurological assessment.

- Administer 100% Oxygen: This is the most critical first aid step. Breathing 100% oxygen helps flush nitrogen from the body, shrinking bubbles and relieving symptoms. Administer it immediately, regardless of oxygen saturation readings.

- Hydration: If the person is conscious, offer non-alcoholic, non-caffeinated fluids to maintain hydration.

- Seeking Professional Help: Contact EMS immediately. Divers should also call the Divers Alert Network (DAN) for expert consultation and coordination with a hyperbaric facility. The Undersea & Hyperbaric Medical Society is another key resource.

Definitive Treatment and Prevention

Definitive care for DCS involves specialized medical intervention, but robust prevention is the best strategy.

Definitive Treatment: Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy

The definitive treatment for DCS is Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy (HBOT). In a specialized chamber, the patient is re-pressurized to shrink the nitrogen bubbles and then breathes 100% oxygen. This high oxygen concentration accelerates the elimination of nitrogen and delivers oxygen to tissues affected by blockages. Treatment follows standardized protocols, like the U.S. Navy Treatment Tables, and is most effective when started within hours of symptom onset.

Preventing DCS: Our Best Defense

Adhering to safety guidelines can significantly reduce your risk of DCS.

- Slow Ascents: Always ascend slowly. For divers, this means following recommended rates (e.g., no faster than 30 feet per minute) to allow for safe off-gassing.

- Using Dive Tables or Computers: Plan your dives and dive your plan. Always stay conservatively within the limits of your dive computer or tables and perform all required decompression stops.

- No-Fly Intervals: Wait before flying after a dive. Follow recommended surface intervals—at least 12-24 hours depending on the dive profile—to prevent DCS triggered by cabin altitude.

- Avoiding Post-Dive Hot Tubs/Saunas: Rapid warming after a dive can promote bubble formation. Wait several hours before taking a hot bath or using a sauna.

- Hydration and Rest: Arrive for your dive well-rested and well-hydrated. Fatigue and dehydration can increase susceptibility.

- Avoid Alcohol: Do not consume alcohol before or immediately after diving.

- Manage Individual Risk Factors: Understand and manage personal risk factors like age, body fat, and pre-existing conditions like a PFO. Dive conservatively and consult a doctor about any health concerns.

If you suspect you have DCS after a dive or flight, seek medical attention immediately. Prompt hyperbaric treatment is crucial for a successful recovery.

For a comprehensive guide to diving science and safety, get your copy of 'Diving Science, Revisited' here: https://www.bestpub.com/view-all-products/product/diving-science-revisited/category_pathway-48.html

DISCLAIMER: Articles are for "EDUCATIONAL PURPOSES ONLY", not to be considered advice or recommendations.